Russian Empire at the beginning of the 19th century, territory, population, socio-economic development of the country. Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary in the 19th century

The history of mankind is a continuous struggle for territorial domination. Great empires either appeared on the political map of the world or disappeared from it. Some of them were destined to leave an indelible mark.

Persian Empire (Achaemenid Empire, 550 - 330 BC)

Cyrus II is considered to be the founder of the Persian Empire. He began his conquests in 550 BC. e. from the subjugation of Media, after which Armenia, Parthia, Cappadocia and the Lydian kingdom were conquered. Did not become an obstacle to the expansion of the empire of Cyrus and Babylon, whose powerful walls fell in 539 BC. e.

Conquering neighboring territories, the Persians tried not to destroy the conquered cities, but, if possible, to preserve them. Cyrus restored the captured Jerusalem, as well as many Phoenician cities, by facilitating the return of the Jews from the Babylonian captivity.

The Persian Empire under Cyrus stretched its possessions from Central Asia to the Aegean Sea. Only Egypt remained unconquered. The country of the pharaohs submitted to the heir of Cyrus Cambyses II. However, the empire reached its heyday under Darius I, who switched from conquests to domestic politics. In particular, the king divided the empire into 20 satrapies, which completely coincided with the territories of the occupied states.

In 330 B.C. e. the weakening Persian Empire fell under the onslaught of the troops of Alexander the Great.

Roman Empire (27 BC - 476)

Ancient Rome was the first state in which the ruler received the title of emperor. Starting with Octavian Augustus, the 500-year history of the Roman Empire had the most direct impact on European civilization, and also left a cultural mark in the countries of North Africa and the Middle East.

The uniqueness of Ancient Rome is that it was the only state whose possessions included the entire Mediterranean coast.

During the heyday of the Roman Empire, its territories stretched from the British Isles to the Persian Gulf. According to historians, by the year 117 the population of the empire reached 88 million people, which was approximately 25% of the total number of inhabitants of the planet.

Architecture, construction, art, law, economics, military affairs, principles state structure Ancient Rome is what the foundation of the entire European civilization is based on. It was in Imperial Rome that Christianity assumed the status of the state religion and began to spread throughout the world.

Byzantine Empire (395 - 1453)

The Byzantine Empire has no equal in the length of its history. Originating at the end of antiquity, it existed until the end of the European Middle Ages. For more than a thousand years, Byzantium has been a kind of link between the civilizations of the East and West, influencing both the states of Europe and Asia Minor.

But if the Western European and Middle Eastern countries inherited the richest material culture of Byzantium, then the Old Russian state turned out to be the successor to its spirituality. Constantinople fell, but the Orthodox world found its new capital in Moscow.

Located at the crossroads of trade routes, rich Byzantium was a coveted land for neighboring states. Having reached its maximum borders in the first centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire, then it was forced to defend its possessions. In 1453, Byzantium could not resist a more powerful enemy - the Ottoman Empire. With the capture of Constantinople, the road to Europe was opened for the Turks.

Arab Caliphate (632-1258)

As a result of the Muslim conquests in the 7th-9th centuries, the theocratic Islamic state of the Arab Caliphate arose on the territory of the entire Middle East region, as well as certain regions of the Transcaucasus, Central Asia, North Africa and Spain. The period of the Caliphate went down in history under the name "Golden Age of Islam", as the time of the highest flowering of Islamic science and culture.

One of the caliphs of the Arab state, Umar I, purposefully secured the character of a militant church for the Caliphate, encouraging religious zeal in his subordinates and forbidding them to own land property in the conquered countries. Umar motivated this by the fact that "the interests of the landowner attract him more to peaceful activities than to war."

In 1036, the invasion of the Seljuk Turks turned out to be disastrous for the Caliphate, but the Mongols completed the defeat of the Islamic state.

Caliph An-Nasir, wishing to expand his possessions, turned to Genghis Khan for help, and without knowing it opened the way for the ruin of the Muslim East to the many thousands of Mongol hordes.

Mongol Empire (1206–1368)

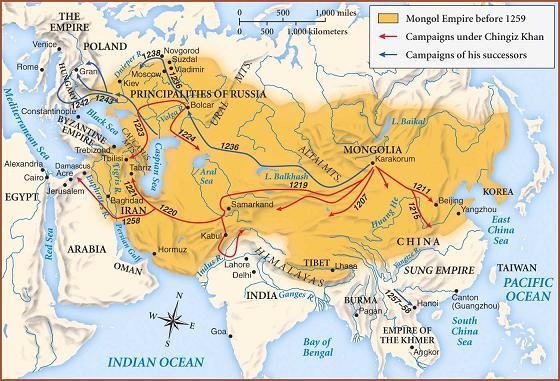

The Mongol Empire is the largest state formation in history in terms of territory.

In the period of its power - by the end of the XIII century, the empire stretched from the Sea of Japan to the banks of the Danube. total area the possessions of the Mongols reached 38 million square meters. km.

Given the vast size of the empire, managing it from the capital, Karakorum, was almost impossible. It is no coincidence that after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, the process of gradual division of the conquered territories into separate uluses began, the most significant of which was the Golden Horde.

The economic policy of the Mongols in the occupied lands was primitive: its essence was reduced to the taxation of tribute to the conquered peoples. All collected went to support the needs of a huge army, according to some sources, reaching half a million people. The Mongol cavalry was the most deadly weapon of the Genghisides, which few armies managed to resist.

The inter-dynastic strife ruined the empire - it was they who stopped the expansion of the Mongols to the West. This was soon followed by the loss of the conquered territories and the capture of the Karakorum by the troops of the Ming Dynasty.

Holy Roman Empire (962-1806)

The Holy Roman Empire is an interstate entity that existed in Europe from 962 to 1806. The core of the empire was Germany, which was joined by the Czech Republic, Italy, the Netherlands, and some regions of France during the period of the highest prosperity of the state.

For almost the entire period of the empire's existence, its structure had the character of a theocratic feudal state, in which emperors claimed supreme power in the Christian world. However, the struggle with the papacy and the desire to possess Italy significantly weakened the central power of the empire.

In the 17th century, Austria and Prussia advanced to leading positions in the Holy Roman Empire. But very soon, the antagonism of two influential members of the empire, which resulted in an aggressive policy, threatened the integrity of their common home. The end of the empire in 1806 was put by the growing France, led by Napoleon.

Ottoman Empire (1299–1922)

In 1299, Osman I created a Turkic state in the Middle East, which was destined to exist for more than 600 years and radically influence the fate of the countries of the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 was the date when the Ottoman Empire finally gained a foothold in Europe.

The period of the highest power of the Ottoman Empire falls on the 16th-17th centuries, but the state achieved the greatest conquests under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

The borders of the empire of Suleiman I stretched from Eritrea in the south to the Commonwealth in the north, from Algiers in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east.

The period from the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 20th century was marked by bloody military conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and Russia. Territorial disputes between the two states mainly unfolded around the Crimea and Transcaucasia. The First World War put an end to them, as a result of which the Ottoman Empire, divided between the countries of the Entente, ceased to exist.

British Empire (1497¬–1949)

The British Empire is the largest colonial power both in terms of territory and population.

The empire reached its greatest extent by the 30s of the 20th century: the land area of the United Kingdom, together with the colonies, totaled 34 million 650 thousand square meters. km., which was approximately 22% of the earth's land. The total population of the empire reached 480 million people - every fourth inhabitant of the Earth was a subject of the British crown.

Many factors contributed to the success of British colonial policy: a strong army and navy, developed industry, and the art of diplomacy. The expansion of the empire had a significant impact on world geopolitics. First of all, this is the spread of British technology, trade, language, and forms of government around the world.

The decolonization of Britain took place after the end of World War II. The country, although it was among the victorious states, was on the verge of bankruptcy. It was only thanks to the American loan of 3.5 billion dollars that Great Britain was able to overcome the crisis, but at the same time it lost world domination and all its colonies.

Russian Empire (1721–1917)

The history of the Russian Empire dates back to October 22, 1721 after the adoption by Peter I of the title of Emperor of All Russia. From that time until 1905, the monarch who became the head of the state was endowed with absolute fullness of power.

In terms of area, the Russian Empire was second only to the Mongol and British empires - 21,799,825 square meters. km, and was the second (after the British) in terms of population - about 178 million people.

The constant expansion of the territory is a characteristic feature of the Russian Empire. But if the advance to the east was mostly peaceful, then in the west and south Russia had to prove its territorial claims through numerous wars - with Sweden, the Commonwealth, the Ottoman Empire, Persia, the British Empire.

The growth of the Russian Empire has always been viewed with particular caution by the West. The appearance of the so-called "Testament of Peter the Great" - a document fabricated in 1812 by French political circles - contributed to the negative perception of Russia. “The Russian State must establish power over all of Europe,” is one of the key phrases of the Testament, which will haunt the minds of Europeans for a long time to come.

deadline

Review – 25 April 23.00Creative work - May 7, 23.00

Lecture 2. Russian Empire in the late XIX-early XX century.

Lecture 2. Russianempire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Socio-economic

position

Political development

Empires (1894-1913)

The first general census of the population of the Russian Empire in 1897

First general censuspopulation of the Russian

Administrative division - 97 provinces.

empire

1897

Census registered in the Russian Empire

125,640,021 inhabitants. By 1913 - 165 million people.

16,828,395 people (13.4%) lived in cities.

Largest cities: St. Petersburg - 1.26 million, Moscow -

1 million, Warsaw - 0.68 million.

The literacy rate was 21.1%, and among men

it was significantly higher than among women (29.3% and

13.1%, respectively).

By religion: Orthodox - 69.3%, Muslims

- 11.1%, Catholics - 9.1% and Jews - 4.2%.

Estates: peasantry - 77.5%, petty bourgeois - 10.7%,

foreigners - 6.6%, Cossacks - 2.3%, nobles - 1.5%,

clergy - 0.5%, honorary citizens - 0.3%,

merchants - 0.2%, others - 0.4%.

Nationalities of Russia (1907-1917) P.P. Kamensky

Class structure of society

NobilityClergy

Guild Merchants

Philistines

Peasants

Odnodvortsy

Cossacks

The class structure of society

Bourgeoisie - 1.5 million peopleProletariat - 2.7 million people. By 1913 -

18 million people

The intelligentsia as a special stratum in

the social structure of society -

725 thousand people

Important:

At the turn of the XIX-XX centuries. social divisionsociety was an interweaving

estate and class structures. Were taking shape

groups of contradictions: nobility-bourgeoisie,

the bourgeoisie is the workers, the government is the people,

intelligentsia - people, intelligentsia -

power. national problems.

The problem of social mobility.

Marginalization. Urbanization. Social

mobility.

Main National Policy Issues

The presence of several faiths (Islam,Buddhism, Catholicism, Lutheranism)

Russification policy regarding

Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish and

other peoples - the rise of nationalism

The Jewish question is the "Pale of Settlement",

discrimination in various fields

activities

Difficult situation in Islamic areas

empires

The turn of the XIX-XX centuries.

The transition from traditional toindustrial society

Overcoming the socio-cultural

backwardness

Democratization of political life

An attempt to form a civil

societies

10. Features of the economic development of Russia

Peculiaritieseconomic development

Later transition to capitalism

Russia

Russia is a country of the second echelon

modernization

Uneven development of the territory

different levels of economic and

sociocultural development

numerous peoples of the empire

Preservation of autocracy, landlord

land tenure, national problems

11. Features of the economic development of Russia

Peculiaritieseconomic development

Rapid pace of development, short deadlines for folding

factory production. Low labor productivity.

Russia

The factory production system evolved without

passing through the previous stages of craft and manufactory.

The growth of industrial output in the 1860-1900s. – 7

once.

The credit system is represented by large commercial

banks

Diversified economy

Russia is characterized not by the export (China, Iran), but by the import of capital

High degree of concentration of production and labor force

Monopolism

State intervention in economic life

Weak inclusion of the agricultural sector in the modernization process

12. Reforms S.Yu. Witte

STRENGTHENING THE ROLESTATES IN

ECONOMY /

Strengthening private

entrepreneurship

1895 - wine

monopoly

1897 - monetary reform

Protectionist policy

attraction

foreign capital

Construction of iron

roads

13. The turn of the XIX-XX centuries.

For the 1890s 5.7 thousand newenterprises

Development of new industrial areas - Yuzhny

(coal-metallurgical) and Baku (oil).

1890s - industrial boom. Construction

Trans-Siberian Railway, CER.

1900-1903 - economic crisis. Closing 3 thousand.

large and medium enterprises.

Investor countries: France, England, Germany, Belgium

monopolization of industrial production and

capital.

Industrial rise 1909-1913

14.

15.

16. Reforms P.A. Stolypin

Community destructionDecree of November 9, 1906

Reorganization

Peasant Bank

Buying them landowners

lands and their resale

into the hands of the peasantry

resettlement

peasants on the outskirts

Courts-martial decree

17. Projects of reforms P.A. Stolypin

Transformation of the peasantvolost courts

national and religious

equality

Introduction of volost zemstvos

Primary Law

schools (compulsory primary

education) (since 1912)

Workers' Insurance Act (1912)

18. State administration of Russia at the beginning of the 20th century (until 1905).

EmperorState Council -

legislative body

The Senate is the oversight body for the rule of law

activity activities

government officials and institutions

Synod

Ministries. Cabinet of Ministers.

19. Autocracy and public life at the beginning of the 20th century.

1901 Politics of the "policeman"socialism” S.V. Zubatov. Creation

professional movement of workers

pursuing economic goals.

The workers need a "king who is for us"

king who "brings in the eight o'clock

working day, raise wages

pay, give all sorts of benefits.

G. Gapon. "Meeting of Russian factory workers of St. Petersburg"

1904

20. Autocracy and public life at the beginning of the 20th century.

Svyatopolk-Mirsky P.D.Minister of the Interior

cases from August 1904

"The development of self-government

and the call of the elected

Petersburg for discussion

as the only

tool that can

enable Russia

develop properly."

Autumn 1904 - "autumn

Spring".

21. Liberal Movement

Banquet campaign of 1904“We consider it absolutely essential that all

the state system was reorganized into

constitutional principles ... and that immediately

However, before the start of the electoral period,

declared a complete and unconditional amnesty for all

political and religious crimes."

Until the beginning of January 1905, 120

similar "banquets", which were attended by about 50

thousand people.

22. Political parties of Russia in n. 20th century

23. "Bloody Sunday"

"The king's prestige is herekilled - that's the meaning

days." M. Gorky.

"Last days

come. Brother

got up on my brother...

The king gave the order

shoot icons"

M. Voloshin

24. Repin I.E. October 17, 1905. (1907)

25. "Manifesto October 17, 1905"

civilfreedom "on the basis of real

privacy, freedom

conscience, words, meetings and unions"

for elections to the State Duma

attracts the general public

All laws must be approved in

Duma, but "elected from the people"

provides an opportunity

actual participation in the supervision of

regularity of actions" of the authorities.

26. Electoral law 11.12.1905

Four electoral curia from the landowners, citypopulation, peasants and workers. Were disenfranchised

choice of women, soldiers, sailors, students,

landless peasants, laborers and some

"foreigners". The system of representation in the Duma was

designed as follows: agricultural

the curia sent one elector from 2 thousand people,

urban - from 7 thousand, peasant - from 30 thousand,

working - from 90 thousand people. Government,

continued to hope that the peasantry would

the backbone of the autocracy, provided him with 45% of all seats in

Duma. Members of the State Duma were elected for a term

for 5 years.

27.

28. Opening of the State Duma and the State Council April 27, 1906

29. State Duma of the Russian Empire

30. State Duma of the Russian Empire

Duma Opening hoursChairman

I

April 27, 1906 -

July 8, 1906

Cadet S.A. Muromtsev

II

February 20, 1907 -

June 2, 1907

Cadet F.A.Golovin

III

November 1, 1907 -

June 9, 1912

Octobrists - N.A. Khomyakov (November

1907-March 1910),

A.I. Guchkov (March 1910-March 1911),

M.V. Rodzianko (March 1911-June 1912)

IV

November 15, 1912 -

February 25, 1917

Octobrist M.V. Rodzianko

31.

32. Literature

Ananyich B.V., Ganelin R.Sh. SergeyYulievich Witte and his time. St. Petersburg:

Dmitry Bulanin, 1999.

Literature about S.Yu. Witte: URL:

http://www.prometeus.nsc.ru/biblio/vitte/r

efer2.ssi

Zyryanov P. N. Pyotr Stolypin:

Political portrait. M., 1992.

Along with the collapse of the Russian Empire, the majority of the population chose to create independent nation-states. Many of them were never destined to remain sovereign, and they became part of the USSR. Others were incorporated into the Soviet state later. And what was the Russian Empire at the beginning XXcentury?

By the end of the 19th century, the territory of the Russian Empire was 22.4 million km2. According to the 1897 census, the population was 128.2 million people, including the population of European Russia - 93.4 million people; The kingdom of Poland - 9.5 million, - 2.6 million, the Caucasus region - 9.3 million, Siberia - 5.8 million, Central Asia - 7.7 million people. More than 100 peoples lived; 57% of the population were non-Russian peoples. The territory of the Russian Empire in 1914 was divided into 81 provinces and 20 regions; there were 931 cities. Part of the provinces and regions was united into governor-generals (Warsaw, Irkutsk, Kiev, Moscow, Amur, Steppe, Turkestan and Finland).

By 1914, the length of the territory of the Russian Empire was 4,383.2 versts (4,675.9 km) from north to south and 10,060 versts (10,732.3 km) from east to west. The total length of land and sea borders is 64,909.5 versts (69,245 km), of which land borders accounted for 18,639.5 versts (19,941.5 km), and sea borders accounted for about 46,270 versts (49,360 km). .4 km).

The entire population was considered subjects of the Russian Empire, the male population (from 20 years old) swore allegiance to the emperor. The subjects of the Russian Empire were divided into four classes ("states"): the nobility, the clergy, urban and rural inhabitants. The local population of Kazakhstan, Siberia and a number of other regions stood out in an independent "state" (foreigners). The emblem of the Russian Empire was a double-headed eagle with royal regalia; national flag - a flag with white, blue and red horizontal stripes; national anthem - "God Save the Tsar". National language - Russian.

In administrative terms, the Russian Empire by 1914 was divided into 78 provinces, 21 regions and 2 independent districts. The provinces and regions were subdivided into 777 counties and districts, and in Finland - into 51 parishes. Counties, districts and parishes, in turn, were divided into camps, departments and sections (2523 in total), as well as 274 Lensmanships in Finland.

Important in the military-political terms of the territory (capital and border) were united in the viceroyalty and general government. Some cities were separated into special administrative units - townships.

Even before the transformation of the Grand Duchy of Moscow into the Russian Tsardom in 1547, at the beginning of the 16th century, Russian expansion began to go beyond its ethnic territory and began to absorb the following territories (the table does not indicate lands lost before the beginning of the 19th century):

|

Territory |

Date (year) of joining the Russian Empire |

Facts |

|

Western Armenia (Asia Minor) |

The territory was ceded in 1917-1918 |

|

|

Eastern Galicia, Bukovina (Eastern Europe) |

In 1915 it was ceded, in 1916 it was partially recaptured, in 1917 it was lost |

|

|

Uryankhai region (Southern Siberia) |

Currently part of the Republic of Tuva |

|

|

Franz Josef Land, Emperor Nicholas II Land, New Siberian Islands (Arctic) |

Archipelagos of the Arctic Ocean, fixed as the territory of Russia by a note of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

|

|

Northern Iran (Middle East) |

Lost as a result of revolutionary events and the Civil War in Russia. Currently owned by the State of Iran |

|

|

Concession in Tianjin |

Lost in 1920. At present, the city of central subordination of the People's Republic of China |

|

|

Kwantung Peninsula (Far East) |

Lost as a result of defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Currently Liaoning Province, China |

|

|

Badakhshan (Central Asia) |

Currently Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous District of Tajikistan |

|

|

Concession in Hankou (Wuhan, East Asia) |

Currently Hubei Province, China |

|

|

Transcaspian region (Central Asia) |

Currently owned by Turkmenistan |

|

|

Adjarian and Kars-Childyr sanjaks (Transcaucasia) |

In 1921 they were ceded to Turkey. Currently Adjara Autonomous Region of Georgia; silts of Kars and Ardahan in Turkey |

|

|

Bayazet (Dogubayazit) sanjak (Transcaucasia) |

In the same year, 1878, it was ceded to Turkey following the results of the Berlin Congress. |

|

|

Principality of Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia, Adrianople Sanjak (Balkans) |

Abolished by the results of the Berlin Congress in 1879. Currently Bulgaria, Marmara region of Turkey |

|

|

Khanate of Kokand (Central Asia) |

Currently Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan |

|

|

Khiva (Khorezm) Khanate (Central Asia) |

Currently Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan |

|

|

including Åland |

Currently Finland, Republic of Karelia, Murmansk, Leningrad regions |

|

|

Tarnopol District of Austria (Eastern Europe) |

Currently Ternopil region of Ukraine |

|

|

Bialystok District of Prussia (Eastern Europe) |

Currently Podlaskie Voivodeship of Poland |

|

|

Ganja (1804), Karabakh (1805), Sheki (1805), Shirvan (1805), Baku (1806), Quba (1806), Derbent (1806), northern part of the Talysh (1809) khanate (Transcaucasia) |

Vassal khanates of Persia, capture and voluntary entry. Fixed in 1813 by an agreement with Persia following the war. Limited autonomy until 1840s. Currently Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh Republic |

|

|

Kingdom of Imereti (1810), Megrelian (1803) and Gurian (1804) principalities (Transcaucasia) |

Kingdom and principalities of Western Georgia (since 1774 independent from Turkey). Protectorates and voluntary entry. They were fixed in 1812 by an agreement with Turkey and in 1813 by an agreement with Persia. Self-government until the end of the 1860s. Currently Georgia, the regions of Samegrelo-Upper Svaneti, Guria, Imereti, Samtskhe-Javakheti |

|

|

Minsk, Kiev, Bratslav, eastern parts of the Vilna, Novogrudok, Beresteisky, Volyn and Podolsky voivodeships of the Commonwealth (Eastern Europe) |

Currently Vitebsk, Minsk, Gomel regions of Belarus; Rivne, Khmelnytsky, Zhytomyr, Vinnitsa, Kyiv, Cherkasy, Kirovohrad regions of Ukraine |

|

|

Crimea, Yedisan, Dzhambailuk, Yedishkul, Lesser Nogai Horde (Kuban, Taman) (Northern Black Sea region) |

Khanate (independent from Turkey since 1772) and nomadic Nogai tribal unions. Annexation, secured in 1792 by treaty as a result of the war. Currently Rostov Region, Krasnodar Territory, Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol; Zaporozhye, Kherson, Nikolaev, Odessa regions of Ukraine |

|

|

Kuril Islands (Far East) |

Tribal unions of the Ainu, bringing into Russian citizenship, finally by 1782. Under the treaty of 1855, the South Kuriles in Japan, under the treaty of 1875 - all the islands. Currently, the North Kuril, Kuril and South Kuril urban districts of the Sakhalin Region |

|

|

Chukotka (Far East) |

Currently Chukotka Autonomous Okrug |

|

|

Tarkov shamkhalate (Northern Caucasus) |

Currently the Republic of Dagestan |

|

|

Ossetia (Caucasus) |

Currently Republic of North Ossetia - Alania, Republic of South Ossetia |

|

|

Big and Small Kabarda |

principalities. In 1552-1570, a military alliance with the Russian state, later vassals of Turkey. In 1739-1774, according to the agreement, it was a buffer principality. Since 1774 in Russian citizenship. Currently Stavropol Territory, Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, Chechen Republic |

|

|

Inflyantsky, Mstislavsky, large parts of Polotsk, Vitebsk voivodeships of the Commonwealth (Eastern Europe) |

Currently Vitebsk, Mogilev, Gomel regions of Belarus, Daugavpils region of Latvia, Pskov, Smolensk regions of Russia |

|

|

Kerch, Yenikale, Kinburn (Northern Black Sea region) |

Fortresses, from the Crimean Khanate by agreement. Recognized by Turkey in 1774 by treaty as a result of the war. The Crimean Khanate gained independence from the Ottoman Empire under the auspices of Russia. Currently, the urban district of Kerch of the Republic of Crimea of Russia, Ochakovsky district of the Nikolaev region of Ukraine |

|

|

Ingushetia (Northern Caucasus) |

Currently Republic of Ingushetia |

|

|

Altai (Southern Siberia) |

Currently Altai region, Republic of Altai, Novosibirsk, Kemerovo, Tomsk regions of Russia, East Kazakhstan region of Kazakhstan |

|

|

Kymenigord and Neishlot flax - Neishlot, Wilmanstrand and Friedrichsgam (Baltic) |

Len, from Sweden by treaty as a result of the war. Since 1809 in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland. Currently Leningrad region of Russia, Finland (region of South Karelia) |

|

|

Junior zhuz (Central Asia) |

Currently West Kazakhstan region of Kazakhstan |

|

|

(Kyrgyz land, etc.) (Southern Siberia) |

Currently Republic of Khakassia |

|

|

Novaya Zemlya, Taimyr, Kamchatka, Commander Islands (Arctic, Far East) |

Currently Arkhangelsk Region, Kamchatka, Krasnoyarsk Territory |

Domestic policy in the first half of the 19th century

Assuming the throne, Alexander solemnly proclaimed that henceforth politics would be based not on the personal will or whim of the monarch, but on strict observance of laws. The population was promised legal guarantees against arbitrariness. Around the king there was a circle of friends, called the Unspoken Committee. It included young aristocrats: Count P. A. Stroganov, Count V. P. Kochubey, N. N. Novosiltsev, Prince A. D. Czartorysky. The aggressively minded aristocracy dubbed the committee "the Jacobin gang." This committee met from 1801 to 1803 and discussed projects for state reforms, the abolition of serfdom, and so on.

During the first period of the reign of Alexander I from 1801 to 1815. much has been done, but much more has been promised. The restrictions imposed by Paul I were lifted. Kazan, Kharkov, St. Petersburg universities were created. Universities were opened in Dorpat and Vilna. In 1804, the Moscow Commercial School was opened. From now on, representatives of all classes could be admitted to educational institutions, at the lower levels education was free, paid from the state budget. The reign of Alexander I was characterized by unconditional religious tolerance, which was extremely important for multinational Russia.

In 1802, the obsolete collegiums, which had been the main organs of executive power since the time of Peter the Great, were replaced by ministries. The first 8 ministries were established: the army, the navy, justice, internal affairs, and finance. Commerce and public education.

In 1810-1811. during the reorganization of the ministries, their number increased, and the functions were even more clearly delineated. In 1802, the Senate was reformed, becoming the highest judicial and controlling body in the system of state administration. He received the right to make "representations" to the emperor about outdated laws. Spiritual affairs were in charge of the Holy Synod, whose members were appointed by the emperor. It was headed by the chief prosecutor, a person, as a rule, close to the king. From military or civilian officials. Under Alexander I, the position of chief prosecutor in 1803-1824. Prince A.N. Golitsyn, who since 1816 was also the Minister of Public Education. The most active supporter of the idea of reforming the public administration system was the state secretary of the Permanent Council, M. M. Speransky. However, he did not enjoy the favor of the emperor for a very long time. The implementation of Speransky's project could contribute to the beginning of the constitutional process in Russia. In total, the project “Introduction to the Code of State Laws” outlined the principle of separation of the legislative, executive and judicial powers by convening representatives of the State Duma and introducing elected judicial instances.

At the same time, he considered it necessary to create a State Council, which would become a link between the emperor and the bodies of central and local self-government. The cautious Speransky endowed all the newly proposed bodies only with deliberative rights and by no means encroached on the fullness of autocratic power. The liberal project of Speransky was opposed by the conservative-minded part of the nobility, which saw in it a danger to the autocratic-feudal system and to their privileged position.

The well-known writer and historian I. M. Karamzin became the ideologist of the conservatives. In practical terms, the reactionary policy was pursued by Count A. A. Arakcheev, close to Alexander I, who, unlike M. M. Speransky, sought to strengthen the personal power of the emperor through the further development of the bureaucratic system.

The struggle between liberals and conservatives ended in victory for the latter. Speransky was removed from business and sent into exile. The only result was the establishment of the State Council, in 1810, which consisted of ministers and other high dignitaries appointed by the emperor. He was given advisory functions in the development of the most important laws. Reforms 1802–1811 did not change the autocratic essence of the Russian political system. They only increased the centralization and bureaucratization of the state apparatus. As before, the emperor was the supreme legislative and executive power.

In subsequent years, the reformist moods of Alexander I were reflected in the introduction of a constitution in the Kingdom of Poland (1815), the preservation of the Sejm and the constitutional structure of Finland, annexed to Russia in 1809, as well as in the creation by N.N. Russian Empire" (1819-1820). The project provided for the separation of branches of power, the introduction of government bodies. Equality of all citizens before the law and the federal principle of government. However, all these proposals remained on paper.

In the last decade of the reign of Alexander I, a conservative trend was increasingly felt in domestic politics. By the name of her guide, she received the name "Arakcheevshchina". This policy was expressed in the further centralization of state administration, in police-repressive measures aimed at the destruction of free thought, in the "cleansing" of universities, in the planting of cane discipline in the army. The most striking manifestation of the policy of Count A. A. Arakcheev was military settlements - a special form of recruiting and maintaining the army.

The purpose of creating military settlements is to achieve self-support and self-reproduction of the army. To ease for the country's budget the burden of maintaining a huge army in peaceful conditions. The first attempts to organize them date back to 1808-1809, but they began to be created en masse in 1815-1816. State-owned peasants of St. Petersburg, Novgorod, Mogilev and Kharkov provinces were transferred to the category of military settlements. Soldiers were also settled here, to whom their families were registered. Wives became villagers, sons from the age of 7 were enrolled as cantonists, and from the age of 18 into actual military service. The whole life of the peasant family was strictly regulated. For the slightest violation of the order, corporal punishment followed. A. A. Arakcheev was appointed chief commander of the military settlements. By 1825, about a third of the soldiers had been transferred to the settlement.

However, the idea of the self-sufficiency of the army failed. The government spent a lot of money on the organization of settlements. The military settlers did not become a special class that expanded the social support of the autocracy, on the contrary, they were worried and rebelled. The government abandoned this practice in subsequent years. Alexander I died in Taganrog in 1825. He had no children. Due to the ambiguity in the issue of succession to the throne in Russia, an emergency situation was created - an interregnum.

The years of the reign of Emperor Nicholas I (1825-1855) are rightly regarded as "the apogee of autocracy". The Nikolaev reign began with the massacre of the Decembrists and ended in the days of the defense of Sevastopol. The replacement of the heir to the throne by Alexander I came as a surprise to Nicholas I, who was not prepared to rule Russia.

On December 6, 1826, the emperor created the first Secret Committee, headed by the Chairman of the State Council V.P. Kochubey. Initially, the committee developed projects for the transformation of higher and local government and the law "on states", that is, on the rights of estates. It was supposed to consider the peasant question. However, in fact, the work of the committee did not give any practical results, and in 1832 the committee ceased its activities.

Nicholas I set the task of concentrating in his hands the solution of both general and private affairs, bypassing the relevant ministries and departments. The principle of the regime of personal power was embodied in His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery. It was divided into several branches that interfered in the political, social and spiritual life of the country.

The codification of Russian legislation was entrusted to M. M. Speransky, returned from exile, who intended to collect and classify all existing laws, to create in principle new system legislation. However, conservative tendencies in domestic politics limited him to a more modest task. Under his leadership, the laws adopted after the Council Code of 1649 were summarized. They were published in the Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire in 45 volumes. In a separate "Code of Laws" (15 volumes), the current laws were placed, which corresponded to the legal situation in the country. All this was also aimed at strengthening the bureaucratization of management.

In 1837-1841. under the leadership of Count P. D. Kiselev, a wide system of measures was carried out - the reform of the management of state peasants. In 1826, a committee was set up to set up educational institutions. Its tasks included: checking the statutes of educational institutions, developing uniform principles of education, determining academic disciplines and manuals. The committee developed the basic principles of government policy in the field of education. They were legally enshrined in the Charter of lower and secondary educational institutions in 1828. Estate, isolation, isolation of each step, restriction in the education of representatives of the lower classes, created the essence of the created education system.

The reaction hit the universities as well. Their network, however, was expanded due to the need for qualified officials. The charter of 1835 liquidated university autonomy, tightened control over the trustees of educational districts, the police and local government. At that time, S.S. Uvarov was the Minister of Public Education, who, in his policy, sought to combine the “protection” of Nicholas I with the development of education and culture.

In 1826, a new censorship charter was issued, which was called "cast iron" by contemporaries. The Main Directorate of Censorship was subordinate to the Ministry of Public Education. The fight against advanced journalism was considered by Nicholas I as one of the top political tasks. One after another, bans on the publication of magazines rained down. 1831 was the date of the termination of the publication of A. A. Delvich's Literary Gazette, in 1832 P. V. Kirievsky's The European was closed, in 1834 the Moscow Telegraph by N. A. Polevoy, and in 1836 " Telescope” by N. I. Nadezhdin.

In the domestic policy of the last years of the reign of Nicholas I (1848-1855), the reactionary-repressive line intensified even more.

By the mid 50s. Russia turned out to be "an ear of clay with feet of clay." This predetermined failures in foreign policy, the defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1856) and caused the reforms of the 60s.

Foreign policy of Russia in the first half of the XIX century.At the turn of the XVIII - XIX centuries. two directions in Russia's foreign policy were clearly defined: the Middle East - the struggle to strengthen its positions in the Transcaucasus, the Black Sea and the Balkans, and the European - Russia's participation in coalition wars against Napoleonic France. One of the first acts of Alexander I after accession to the throne was the restoration of relations with England. But Alexander I did not want to come into conflict with France either. The normalization of relations with England and France allowed Russia to intensify its activities in the Middle East, mainly in the region of the Caucasus and Transcaucasia.

According to the manifesto of Alexander I of September 12, 1801, the Georgian ruling dynasty of the Bagratids lost the throne, the control of Kartli and Kakheti passed to the Russian governor. Tsarist administration was introduced in Eastern Georgia. In 1803-1804. under the same conditions, the rest of Georgia - Mengrelia, Guria, Imeretia - became part of Russia. Russia received strategically important territory for strengthening its positions in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia. The completion in 1814 of the construction of the Georgian Military Highway, which connected the Transcaucasus with European Russia, was of great importance not only in the strategic, but also in the economic sense.

The annexation of Georgia pushed Russia against Iran and the Ottoman Empire. The hostile attitude of these countries towards Russia was fueled by the intrigues of England. The war with Iran that began in 1804 was successfully waged by Russia: already during 1804-1806. the main part of Azerbaijan was annexed to Russia. The war ended with the annexation in 1813 of the Talysh Khanate and the Mugan steppe. According to the Peace of Gulistan, signed on October 24, 1813, Iran recognized the assignment of these territories to Russia. Russia was granted the right to keep its military vessels on the Caspian Sea.

In 1806, the war between Russia and Turkey began, which relied on the help of France, which supplied it with weapons. The reason for the war was the removal in August 1806 from the posts of the rulers of Moldavia and Wallachia at the insistence of the Napoleonic General Sebastiani, who arrived in Turkey. In October 1806, Russian troops under the command of General I. I. Mikhelson occupied Moldavia and Wallachia. In 1807, the squadron of D.N. Senyavin defeated the Ottoman fleet, but then the diversion of the main forces of Russia to participate in the anti-Napoleonic coalition did not allow the Russian troops to develop success. Only when M. I. Kutuzov was appointed commander of the Russian army in 1811 did the hostilities take a completely different turn. Kutuzov concentrated the main forces at the Ruschuk fortress, where on June 22, 1811 he inflicted a crushing defeat on the Ottoman Empire. Then, with successive blows, Kutuzov defeated in parts the main forces of the Ottomans along the left bank of the Danube, their remnants laid down their arms and surrendered. On May 28, 1812, Kutuzov signed a peace treaty in Bucharest, according to which Moldavia was ceded to Russia, which later received the status of the Bessarabia region. Serbia, which rose to fight for independence in 1804 and was supported by Russia, was presented with autonomy.

In 1812, the eastern part of Moldova became part of Russia. Its western part (beyond the Prut River), under the name of the Principality of Moldavia, remained in vassal dependence on the Ottoman Empire.

In 1803-1805. the international situation in Europe sharply worsened. The period of the Napoleonic wars begins, in which all European countries were involved, incl. and Russia.

At the beginning of the XIX century. Almost all of central and southern Europe was under Napoleon's rule. In foreign policy, Napoleon expressed the interests of the French bourgeoisie, which competed with the British bourgeoisie in the struggle for world markets and for the colonial division of the world. Anglo-French rivalry acquired a pan-European character and took a leading place in international relations at the beginning of the 19th century.

The proclamation in 1804 on May 18 of Napoleon as emperor further inflamed the situation. April 11, 1805 was concluded. The Anglo-Russian military convention, according to which Russia was obliged to put up 180 thousand soldiers, and England to pay a subsidy to Russia in the amount of 2.25 million pounds sterling and participate in land and sea military operations against Napoleon. Austria, Sweden and the Kingdom of Naples joined this convention. However, only Russian and Austrian troops numbering 430 thousand soldiers were sent against Napoleon. Having learned about the movement of these troops, Napoleon withdrew his army in the Boulogne camp and quickly moved it to Bavaria, where the Austrian army was located under the command of General Mack and utterly defeated it at Ulm.

The commander of the Russian army, M. I. Kutuzov, taking into account Napoleon's fourfold superiority in strength, through a series of skillful maneuvers, avoided a major battle and, having made a difficult 400-kilometer march, joined up with another Russian army and Austrian reserves. Kutuzov proposed to withdraw the Russian-Austrian troops further east in order to gather enough strength for the successful conduct of hostilities, however, the emperors Franz and Alexander I, who were with the army, insisted on a general battle. On November 20, 1805, it took place at Austerlitz (Czech Republic) and ended in victory Napoleon. Austria capitulated and made a humiliating peace. The coalition actually broke up. Russian troops were withdrawn to the borders of Russia and Russian-French peace negotiations began in Paris. On July 8, 1806, a peace treaty was concluded in Paris, but Alexander I refused to ratify it.

In mid-September 1806, a fourth coalition was formed against France (Russia, Great Britain, Prussia and Sweden). In the battle of Jena and Auerstedt, the Prussian troops were completely defeated. Almost all of Prussia was occupied by French troops. The Russian army had to fight alone for 7 months against the superior forces of the French. The most significant were the battles of Russian troops with the French in East Prussia on January 26-27 at Preussisch-Eylau and on June 2, 1807 near Friedland. During these battles, Napoleon managed to push the Russian troops back to the Neman, but he did not dare to enter Russia and offered to make peace. The meeting between Napoleon and Alexander I took place in Tilsit (on the Neman) at the end of June 1807. The peace treaty was concluded on June 25, 1807.

Joining the continental blockade caused severe damage to the Russian economy, since England was its main trading partner. The conditions of the Peace of Tilsit caused strong discontent both in conservative circles and in the advanced circles of Russian society. A serious blow was dealt to Russia's international prestige. The painful impression of the Tilsit Peace was to some extent “compensated” by the successes in the Russian-Swedish war of 1808-1809, which was the result of the Tilsit agreements.

The war began on February 8, 1808 and demanded a great effort from Russia. At first, military operations were successful: in February-March 1808, the main urban centers and fortresses of Southern Finland were occupied. Then hostilities stopped. By the end of 1808, Finland was liberated from the Swedish troops, and in March, the 48,000th corps of M. B. Barclay de Tolly, having made the transition on the ice of the Gulf of Bothnia, approached Stockholm. On September 5, 1809, in the city of Friedrichsgam, a peace was concluded between Russia and Sweden, under the terms of which Finland and the Aland Islands passed to Russia. At the same time, the contradictions between France and Russia gradually deepened.

A new war between Russia and France was becoming inevitable. The main motive for unleashing the war was Napoleon's desire for world domination, on the way to which Russia stood.

On the night of June 12, 1812, the Napoleonic army crossed the Neman and invaded Russia. The left flank of the French army consisted of 3 corps under the command of MacDonald, advancing on Riga and Petersburg. The main, central group of troops, consisting of 220 thousand people, led by Napoleon, attacked Kovno and Vilna. Alexander I at that time was in Vilna. At the news of France crossing the Russian border, he sent General A. D. Balashov to Napoleon with peace proposals, but was refused.

Usually, Napoleon's wars were reduced to one or two general battles, which decided the fate of the company. And for this, Napoleon's calculation was reduced to using his numerical superiority to smash the dispersed Russian armies one by one. On June 13, French troops occupied Kovno, and on June 16 Vilna. At the end of June, Napoleon's attempt to encircle and destroy the army of Barclay de Tolly in the Drissa camp (on the Western Dvina) failed. Barclay de Tolly, by a successful maneuver, led his army out of the trap that the Drissa camp could have turned out to be and headed through Polotsk to Vitebsk to join the army of Bagration, who was retreating south in the direction of Bobruisk, Novy Bykhov and Smolensk. The difficulties of the Russian army were aggravated by the lack of a unified command. On June 22, after heavy rearguard battles, the armies of Barclay da Tolly and Bagration united in Smolensk.

The stubborn battle of the Russian rearguard with the advancing advanced units of the French army on August 2 near Krasnoy (west of Smolensk) allowed the Russian troops to strengthen Smolensk. On August 4-6, a bloody battle for Smolensk took place. On the night of August 6, the burned and destroyed city was abandoned by Russian troops. In Smolensk, Napoleon decided to advance on Moscow. On August 8, Alexander I signed a decree appointing M. I. Kutuzov as commander-in-chief of the Russian army. Nine days later, Kutuzov arrived in the army.

For the general battle, Kutuzov chose a position near the village of Borodino. On August 24, the French army approached the advanced fortification in front of the Borodino field - the Shevardinsky redoubt. A heavy battle ensued: 12,000 Russian soldiers held back the onslaught of a 40,000-strong French detachment all day. This battle helped to strengthen the left flank of the Borodino position. The battle of Borodino began at 5 o'clock in the morning on August 26 with the attack of the French division of General Delzon on Borodino. Only by 16 o'clock was the Raevsky redoubt captured by the French cavalry. By evening, Kutuzov gave the order to withdraw to a new line of defense. Napoleon stopped the attacks, limiting himself to artillery cannonade. As a result of the Battle of Borodino, both armies suffered heavy losses. The Russians lost 44 thousand, and the French 58 thousand people.

On September 1 (13), a military council was convened in the village of Fili, at which Kutuzov made the only right decision - to leave Moscow in order to save the army. The next day the French army approached Moscow. Moscow was empty: no more than 10 thousand inhabitants remained in it. On the same night, fires broke out in various parts of the city, which raged for a whole week. The Russian army, leaving Moscow, first moved to Ryazan. Near Kolomna, Kutuzov, leaving a barrier of several Cossack regiments, turned onto the Starokaluga road and withdrew his army from the attack of the pressing French cavalry. The Russian army entered Tarutino. On October 6, Kutuzov suddenly struck at Murat's corps, which was stationed on the river. Chernishne is not far from Tarutina. The defeat of Murat forced Napoleon to accelerate the movement of the main forces of his army to Kaluga. Kutuzov sent his troops to cross him to Maloyaroslavets. On October 12, a battle took place near Maloyaroslavets, which forced Napoleon to abandon the movement to the south and turn to Vyazma on the old Smolensk road devastated by the war. The retreat of the French army began, which later turned into a flight, and its parallel pursuit by the Russian army.

From the moment Napoleon invaded Russia, a people's war broke out in the country against foreign invaders. After leaving Moscow, and especially during the period of the Tarutino camp, the partisan movement assumed a wide scope. Partisan detachments, having launched a "small war", disrupted enemy communications, performed the role of reconnaissance, sometimes gave real battles and actually blocked the retreating French army.

Retreating from Smolensk to the river. Berezina, the French army still retained combat effectiveness, although it suffered heavy losses from hunger and disease. After crossing the river Berezina already began a disorderly flight of the remnants of the French troops. On December 5, in Sorgani, Napoleon handed over command to Marshal Murat, and he hurried to Paris. On December 25, 1812, the tsar's manifesto was published announcing the end of the Patriotic War. Russia was the only country in Europe capable of not only resisting Napoleonic aggression, but also inflicting a crushing defeat on it. But this victory came at a high cost to the people. 12 provinces that became the scene of hostilities were devastated. Such ancient cities as Moscow, Smolensk, Vitebsk, Polotsk, etc., were burnt and devastated.

To ensure its security, Russia continued hostilities and led the movement for the liberation of the European peoples from French domination.

In September 1814, the Congress of Vienna opened, at which the victorious powers decided on the post-war structure of Europe. It was difficult for the allies to agree among themselves, because. sharp contradictions arose, mainly on territorial issues. The work of the congress was interrupted due to the flight of Napoleon from Fr. Elba and the restoration of his power in France for 100 days. By combined efforts, the European states inflicted a final defeat on him at the Battle of Waterloo in the summer of 1815. Napoleon was captured and exiled to about. St. Helena off the west coast of Africa.

The decisions of the Congress of Vienna led to the return of the old dynasties in France, Italy, Spain and other countries. From most of the Polish lands, the Kingdom of Poland was created as part of the Russian Empire. In September 1815, the Russian Emperor Alexander I, the Austrian Emperor Franz and the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III signed an act establishing the Holy Alliance. Alexander I himself was its author. The text of the Union contained the obligations of Christian monarchs to provide each other with all possible assistance. Political goals - support of the old monarchical dynasties based on the principle of legitimism (recognition of the legitimacy of maintaining their power), the fight against revolutionary movements in Europe.

At the Congresses of the Union during the years from 1818 to 1822. the suppression of revolutions was authorized in Naples (1820-1821), Piedmont (1821), Spain (1820-1823). However, these actions were aimed at maintaining peace and stability in Europe.

The news of the uprising in St. Petersburg in December 1825 was perceived by the Shah's government as a good moment to unleash hostilities against Russia. On July 16, 1826, the 60,000-strong Iranian army invaded Transcaucasia without declaring war and began a rapid movement towards Tbilisi. But soon she was stopped and began to suffer defeat after defeat. At the end of August 1826, Russian troops under the command of A.P. Yermolov completely cleared Transcaucasia from Iranian troops and military operations were transferred to the territory of Iran.

Nicholas I, not trusting Yermolov (he suspected him of having connections with the Decembrists), transferred the command of the troops of the Caucasus District to I.F. Paskevich. In April 1827, the offensive of Russian troops began in Eastern Armenia. The local Armenian population rose to help the Russian troops. In early July, Nakhchivan fell, and in October 1827, Erivan - the largest fortresses in the center of the Nakhichevan and Erivan khanates. Soon all of Eastern Armenia was liberated by Russian troops. At the end of October 1827, Russian troops occupied Tabriz, the second capital of Iran, and quickly advanced towards Tehran. Panic broke out among the Iranian troops. Under these conditions, the Shah's government was forced to agree to the terms of peace proposed by Russia. On February 10, 1828, the Turkmanchay peace treaty between Russia and Iran was signed. According to the Turkmanchay Treaty, the Nakhichevan and Erivan khanates joined Russia.

In 1828, the Russian-Turkish war began, which was extremely difficult for Russia. The troops, accustomed to parade ground art, technically poorly equipped and led by mediocre generals, initially failed to achieve any significant success. The soldiers were starving, diseases raged among them, from which more people died than from enemy bullets. In the company of 1828, at the cost of considerable efforts and losses, they managed to occupy Wallachia and Moldavia, cross the Danube and take the fortress of Varna.

The campaign of 1829 was more successful. The Russian army crossed the Balkans and at the end of June, after a long siege, captured the strong fortress of Silistria, then Shumla, and in July Burgas and Sozopol. In Transcaucasia, Russian troops besieged the fortresses of Kars, Ardagan, Bayazet and Erzerum. On August 8, Adrianople fell. Nicholas I hurried the commander-in-chief of the Russian army Dibich with the conclusion of peace. On September 2, 1829, a peace treaty was concluded in Adrianople. Russia received the mouth of the Danube, the Black Sea coast of the Caucasus from Anapa to the approaches to Batum. After the annexation of Transcaucasia, the Russian government faced the task of ensuring a stable situation in the North Caucasus. Under Alexander I, the general began to advance deep into Chechnya and Dagestan, building military strongholds. The local population was driven to the construction of fortresses, fortified points, the construction of roads and bridges. The uprisings in Kabarda and Adygea (1821-1826) and Chechnya (1825-1826) were the result of the policy pursued, which, however, were subsequently suppressed by Yermolov's corps.

An important role in the movement of the mountaineers of the Caucasus was played by Muridism, which became widespread among the Muslim population of the North Caucasus in the late 1920s. 19th century It implied religious fanaticism and an uncompromising struggle against the "infidels", which gave it a nationalistic character. In the North Caucasus, it was directed exclusively against Russians and was most widespread in Dagestan. A peculiar state - Immat - has developed here. In 1834, Shamil became the imam (head of state). Under his leadership, the struggle against the Russians intensified in the North Caucasus. It continued for 30 years. Shamil managed to unite the broad masses of the highlanders, to carry out a number of successful operations against the Russian troops. In 1848 his power was declared hereditary. It was the time of Shamil's greatest successes. But in the late 40s - early 50s, the urban population, dissatisfied with the feudal-theocratic order in Shamil's imamate, began to gradually move away from the movement, and Shamil began to fail. The highlanders left Shamil with whole auls and stopped the armed struggle against the Russian troops.

Even Russia's failures in the Crimean War did not ease the situation of Shamil, who tried to actively assist the Turkish army. His raids on Tbilisi failed. The peoples of Kabarda and Ossetia also did not want to join Shamil and oppose Russia. In 1856-1857. Chechnya fell away from Shamil. Uprisings began against Shamil in Avaria and Northern Dagestan. Under the onslaught of the troops, Shamil retreated to Southern Dagestan. On April 1, 1859, the troops of General Evdokimov took Shamil's "capital" - the village of Vedeno and destroyed it. Shamil with 400 murids took refuge in the village of Gunib, where on August 26, 1859, after a long and stubborn resistance, he surrendered. The Imamat ceased to exist. In 1863-1864 Russian troops occupied the entire territory along the northern slope of the Caucasus Range and crushed the resistance of the Circassians. The Caucasian war is over.

For the European absolutist states, the problem of combating the revolutionary danger was dominant in their foreign policy, it was connected with the main task of their domestic policy - the preservation of the feudal-serf order.

In 1830-1831. a revolutionary crisis arose in Europe. On July 28, 1830, a revolution broke out in France, overthrowing the Bourbon dynasty. Having learned about it, Nicholas I began to prepare the intervention of European monarchs. However, the delegations sent by Nicholas I to Austria and Germany returned with nothing. The monarchs did not dare to accept the proposals, believing that this intervention could result in serious social upheavals in their countries. European monarchs recognized the new French king, Louis Philippe of Orleans, as well as later Nicholas I. In August 1830, a revolution broke out in Belgium, which declared itself an independent kingdom (previously Belgium was part of the Netherlands).

Under the influence of these revolutions, in November 1830, an uprising broke out in Poland, caused by the desire to return the independence of the borders of 1792. Prince Konstantin managed to escape. A provisional government of 7 people was formed. The Polish Sejm, which met on January 13, 1831, proclaimed the “detronization” (deprivation of the Polish throne) of Nicholas I and the independence of Poland. Against the 50,000 rebel army, a 120,000 army was sent under the command of I. I. Dibich, who on February 13 inflicted a major defeat on the Poles near Grokhov. On August 27, after a powerful artillery cannonade, the assault on the suburbs of Warsaw - Prague began. The next day, Warsaw fell, the uprising was crushed. The constitution of 1815 was annulled. According to the Limited Statute published on February 14, 1832, the Kingdom of Poland was declared an integral part of the Russian Empire. The administration of Poland was entrusted to the Administrative Council, headed by the emperor's viceroy in Poland, I.F. Paskevich.

In the spring of 1848 a wave of bourgeois-democratic revolutions engulfed Germany, Austria, Italy, Wallachia and Moldavia. At the beginning of 1849 a revolution broke out in Hungary. Nicholas I took advantage of the request of the Austrian Habsburgs for help in suppressing the Hungarian revolution. At the beginning of May 1849, 150 thousand army of I.F. Paskevich was sent to Hungary. A significant preponderance of forces allowed the Russian and Austrian troops to suppress the Hungarian revolution.

Especially acute for Russia was the question of the regime of the Black Sea straits. In the 30-40s. 19th century Russian diplomacy waged a tense struggle for the most favorable conditions in resolving this issue. In 1833, the Unkar-Iskelesi Treaty was concluded between Turkey and Russia for a period of 8 years. Under this treaty, Russia received the right to free passage of its warships through the straits. In the 1940s, the situation changed. On the basis of a number of agreements with European states, the straits were closed to all military fleets. This had a severe effect on the Russian fleet. He was locked in the Black Sea. Russia, relying on its military might, sought to re-solve the problem of the straits and strengthen its position in the Middle East and the Balkans. The Ottoman Empire wanted to return the territories lost as a result of the Russian-Turkish wars at the end of the 18th - the first half of the 19th century.

Britain and France hoped to crush Russia as a great power and deprive her of influence in the Middle East and the Balkan Peninsula. In turn, Nicholas I sought to use the conflict that had arisen for a decisive offensive against the Ottoman Empire, believing that he would have to wage war with one weakened empire, he hoped to agree with England on the division, in his words: "the legacy of a sick person." He counted on the isolation of France, as well as on the support of Austria for the "service" rendered to her in suppressing the revolution in Hungary. His calculations were wrong. England did not go along with his proposal to divide the Ottoman Empire. Nicholas I's calculation that France did not have sufficient military forces to pursue an aggressive policy in Europe was also erroneous.

In 1850, a pan-European conflict began in the Middle East, when disputes broke out between the Orthodox and Catholic churches about which of the churches had the right to own the keys to the Bethlehem temple, to possess other religious monuments in Jerusalem. The Orthodox Church was supported by Russia, and the Catholic Church by France. The Ottoman Empire, which included Palestine, sided with France. This caused sharp discontent in Russia and Nicholas I. A special representative of the tsar, Prince A. S. Menshikov, was sent to Constantinople. He was instructed to obtain privileges for the Russian Orthodox Church in Palestine and the right to patronize the Orthodox, subjects of Turkey. However, his ultimatum was rejected.

Thus, the dispute over the Holy Places served as a pretext for the Russian-Turkish, and later the all-European war. To put pressure on Turkey in 1853, Russian troops occupied the Danubian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. In response, the Turkish Sultan in October 1853, supported by England and France, declared war on Russia. Nicholas I published the Manifesto on the war with the Ottoman Empire. Military operations were deployed on the Danube and in Transcaucasia. On November 18, 1853, Admiral P.S. Nakhimov, at the head of a squadron of six battleships and two frigates, defeated the Turkish fleet in the Sinop Bay and destroyed the coastal fortifications. The brilliant victory of the Russian fleet at Sinop was the reason for the direct intervention of England and France in the military conflict between Russia and Turkey, which was on the verge of defeat. In January 1854, a 70,000 Anglo-French army was concentrated in Varna. At the beginning of March 1854, England and France presented Russia with an ultimatum to clear the Danube principalities, and, having received no answer, declared war on Russia. Austria, for its part, signed with the Ottoman Empire on the occupation of the Danubian principalities and moved an army of 300,000 to their borders, threatening Russia with war. The demand of Austria was supported by Prussia. At first, Nicholas I refused, but the commander-in-chief of the Danube Front, I.F. Paskevich, persuaded him to withdraw troops from the Danubian principalities, which were soon occupied by Austrian troops.

The main goal of the combined Anglo-French command was the capture of the Crimea and Sevastopol, the Russian naval base. On September 2, 1854, the allied troops began landing on the Crimean peninsula near Evpatoria, consisting of 360 ships and 62,000 troops. Admiral P.S. Nakhimov ordered the sinking of the entire sailing fleet in the Sevastopol Bay in order to interfere with the Allied ships. 52 thousand Russian troops, of which 33 thousand with 96 guns from Prince A. S. Menshikov, were located on the entire Crimean peninsula. Under his leadership, the battle on the river. Alma in September 1854, the Russian troops lost. By order of Menshikov, they passed through Sevastopol, and retreated to Bakhchisarai. On September 13, 1854, the siege of Sevastopol began, which lasted 11 months.

The defense was headed by the chief of staff of the Black Sea Fleet, Vice Admiral V. A. Kornilov, and after his death, at the very beginning of the siege, by P. S. Nakhimov, who was mortally wounded on June 28, 1855. Inkerman (November 1854), attack on Evpatoria (February 1855), battle on the Black River (August 1855). These military actions did not help the Sevastopol residents. In August 1855, the last assault on Sevastopol began. After the fall of the Malakhov Kurgan, it was hopeless to continue the defense. In the Caucasian theater, hostilities developed more successfully for Russia. After the defeat of Turkey in Transcaucasia, Russian troops began to operate on its territory. In November 1855, the Turkish fortress of Kars fell. The conduct of hostilities was stopped. Negotiations began.

On March 18, 1856, the Paris peace treaty was signed, according to which the Black Sea was declared neutral. Only the southern part of Bessarabia was torn away from Russia, however, she lost the right to protect the Danubian principalities in Serbia. With the "neutralization" of France, Russia was forbidden to have naval forces, arsenals and fortresses on the Black Sea. This dealt a blow to the security of the southern borders. The defeat in the Crimean War had a significant impact on the alignment of international forces and on the internal situation of Russia. The defeat summed up the sad end of Nicholas' rule, stirred up the public masses and forced the government to work hard on reforming the state.

At the beginning of the XIX century. there was an official consolidation of the boundaries of Russian possessions in North America and northern Europe. The Petersburg conventions of 1824 defined the borders with the American () and English possessions. The Americans pledged not to settle north of 54°40′ N. sh. on the coast, and the Russians - to the south. The border of Russian and British possessions ran along the Pacific coast from 54 ° N. sh. up to 60° s. sh. at a distance of 10 miles from the edge of the ocean, taking into account all the curves of the coast. The St. Petersburg Russian-Swedish Convention of 1826 established the Russian-Norwegian border.

New wars with Turkey and Iran led to further expansion of the territory of the Russian Empire. According to the Akkerman Convention with Turkey in 1826, it secured Sukhum, Anaklia and Redut-Kale. In accordance with the Adrianople Peace Treaty of 1829, Russia received the mouth of the Danube and the Black Sea coast from the mouth of the Kuban to the post of St. Nicholas, including Anapa and Poti, as well as the Akhaltsikhe pashalik. In the same years, Balkaria and Karachay joined Russia. In 1859-1864. Russia included Chechnya, mountainous Dagestan and mountain peoples (Circassians, etc.), who waged wars with Russia for their independence.

After the Russian-Persian war of 1826-1828. Russia received Eastern Armenia (Erivan and Nakhichevan khanates), which was recognized by the Turkmenchay Treaty of 1828.

The defeat of Russia in the Crimean War with Turkey, which acted in alliance with Great Britain, France and the Kingdom of Sardinia, led to the loss of the mouth of the Danube and the southern part of Bessarabia, which was approved by the Peace of Paris in 1856. At the same time, the Black Sea was recognized as neutral. Russian-Turkish war 1877-1878 ended with the annexation of Ardagan, Batum and Kars and the return of the Danubian part of Bessarabia (without the mouths of the Danube).

The borders of the Russian Empire in the Far East were established, which had previously been largely uncertain and controversial. According to the Shimoda Treaty with Japan in 1855, the Russian-Japanese maritime border was drawn in the area of the Kuril Islands along the Friza Strait (between the islands of Urup and Iturup), and Sakhalin Island was recognized as undivided between Russia and Japan (in 1867 it was declared joint possession of these countries). The delimitation of Russian and Japanese island possessions continued in 1875, when Russia, under the Treaty of Petersburg, ceded the Kuril Islands (to the north of the Frieze Strait) to Japan in exchange for recognizing Sakhalin as a possession of Russia. However, after the war with Japan in 1904-1905. According to the Treaty of Portsmouth, Russia was forced to cede to Japan the southern half of Sakhalin Island (from the 50th parallel).

Under the terms of the Aigun (1858) treaty with China, Russia received territories along the left bank of the Amur from the Argun to the mouth, previously considered undivided, and Primorye (Ussuri Territory) was recognized as a common possession. The Beijing Treaty of 1860 formalized the final annexation of Primorye to Russia. In 1871, Russia annexed the Ili region with the city of Ghulja, which belonged to the Qing Empire, but after 10 years it was returned to China. At the same time, the border in the area of \u200b\u200bLake Zaysan and the Black Irtysh was corrected in favor of Russia.

In 1867, the Tsarist government ceded all of its colonies to the United States of North America for $7.2 million.

From the middle of the XIX century. continued what had been started in the 18th century. promotion of Russian possessions in Central Asia. In 1846, the Kazakh Senior Zhuz (Great Horde) announced the voluntary acceptance of Russian citizenship, and in 1853 the Kokand fortress Ak-Mechet was conquered. In 1860, the annexation of Semirechye was completed, and in 1864-1867. parts of the Kokand Khanate (Chimkent, Tashkent, Khojent, Zachirchik Territory) and the Emirate of Bukhara (Ura-Tyube, Jizzakh, Yany-Kurgan) were annexed. In 1868, the Emir of Bukhara recognized himself as a vassal of the Russian Tsar, and the Samarkand and Katta-Kurgan districts of the emirate and the Zeravshan region were annexed to Russia. In 1869, the coast of the Krasnovodsk Bay was annexed to Russia, and the following year, the Mangyshlak Peninsula. According to the Gendemian peace treaty with the Khiva Khanate in 1873, the latter recognized vassal dependence on Russia, and the lands on the right bank of the Amu Darya became part of Russia. In 1875, the Kokand Khanate became a vassal of Russia, and in 1876 it was included in the Russian Empire as the Fergana region. In 1881-1884. the lands inhabited by Turkmens were annexed to Russia, and in 1885 - the Eastern Pamirs. Agreements of 1887 and 1895. Russian and Afghan possessions were demarcated along the Amu Darya and in the Pamirs. Thus, the formation of the border of the Russian Empire in Central Asia was completed.

In addition to the lands annexed to Russia as a result of wars and peace treaties, the country's territory increased due to newly discovered lands in the Arctic: in 1867, Wrangel Island was discovered, in 1879-1881. - the De Long Islands, in 1913 - the Severnaya Zemlya Islands.

Pre-revolutionary changes in the Russian territory ended with the establishment of a protectorate over the Uryankhai region (Tuva) in 1914.

Geographical exploration, discoveries and mapping

European part

Of the geographical discoveries in the European part of Russia, the discovery of the Donetsk Ridge and the Donetsk coal basin, made by E.P. Kovalevsky in 1810-1816, should be mentioned. and in 1828

Despite some setbacks (in particular, the defeat in the Crimean War of 1853-1856 and the loss of territory as a result of Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905) By the beginning of the First World War, the Russian Empire had vast territories and was the largest country in the world in terms of area.

Academic expeditions of V. M. Severgin and A. I. Sherer in 1802-1804. to the north-west of Russia, to Belarus, the Baltic states and Finland were devoted mainly to mineralogical research.

The period of geographical discoveries in the inhabited European part of Russia is over. In the 19th century expeditionary research and their scientific generalization were mainly thematic. Of these, one can name the zoning (mainly agricultural) of European Russia into eight latitudinal bands, proposed by E.F. Kankrin in 1834; botanical and geographical zoning of European Russia by R. E. Trautfetter (1851); studies of the natural conditions of the Baltic and Caspian Seas, the state of fishing and other industries there (1851-1857), carried out by K. M. Baer; the work of N. A. Severtsov (1855) on the fauna of the Voronezh province, in which he showed deep connections between the animal world and physical and geographical conditions, and also established patterns of distribution of forests and steppes in connection with the nature of the relief and soils; classical soil studies by VV Dokuchaev in the chernozem zone, begun in 1877; a special expedition led by V. V. Dokuchaev, organized by the Forest Department for a comprehensive study of the nature of the steppes and finding ways to combat drought. This expedition was the first to use stationary method research.

Caucasus

The annexation of the Caucasus to Russia necessitated the exploration of new Russian lands, which were poorly studied. In 1829, the Caucasian expedition of the Academy of Sciences, led by A. Ya. Kupfer and E. Kh. Lenz, explored the Rocky Range in the Greater Caucasus, determined the exact heights of many mountain peaks of the Caucasus. In 1844-1865. the natural conditions of the Caucasus were studied by G. V. Abikh. He studied in detail the orography and geology of the Greater and Lesser Caucasus, Dagestan, the Colchis lowland, and compiled the first general orographic scheme of the Caucasus.

Ural

The description of the Middle and Southern Urals, made in 1825-1836, is among the works that developed the geographical idea of the Urals. A. Ya. Kupfer, E. K. Hoffman, G. P. Gelmersen; the publication of "The Natural History of the Orenburg Territory" by E. A. Eversman (1840), which gives a comprehensive description of the nature of this territory with a well-founded natural division; Expedition of the Russian Geographical Society to the Northern and Polar Urals (E.K. Gofman, V.G. Bragin), during which the Konstantinov Kamen peak was discovered, the Pai-Khoi ridge was discovered and explored, an inventory was compiled that served as the basis for mapping the studied part of the Urals . A notable event was the journey in 1829 of the outstanding German naturalist A. Humboldt to the Urals, Rudny Altai and to the shores of the Caspian Sea.

Siberia

In the 19th century continued exploration of Siberia, many areas of which were studied very poorly. In Altai, in the 1st half of the century, the sources of the river were discovered. Lake Teletskoye (1825-1836, A. A. Bunge, F. V. Gebler), the Chulyshman and Abakan rivers (1840-1845, P. A. Chikhachev) were explored. During his travels, P. A. Chikhachev carried out physical-geographical and geological studies.