Jewish Authors. Jewish poets. Barto Agniya Lvovna - Gitel Leibovna Volova

Every adult began his acquaintance with literature in childhood, leafing through colorful books of fairy tales. Of course, in adulthood, fairy tales give way to novels and short stories, but the plots of your favorite fairy tales remain in your memory for many years. Carried away by fabulous events, children from an early age learn to understand the difference between good and evil, get out of difficult situations and get acquainted with the world in which they will live. But all this can be found not in every book and not in every author, because only a person of special talent can put deep meaning into a simple form, of which there have been not so many throughout history. There were even fewer Jewish storytellers, but the contribution of each to the transmission and preservation of Jewish traditions and worldview cannot be overestimated.

It is difficult to determine when the tradition of telling tales appeared among the Jews, however, the most ancient tales, serious, spiritual and valuable, can be called the Haggadic Midrash. These old instructive stories served as the basis for many fairy tales known to us and still occupy the minds of children and adults. The oral Torah served as the source of plots and heroes of such stories, but over time, the stories were modified, supplemented or reduced, without departing, however, from their original essence. Jews not only told and retold fairy tales, but also collected them and wrote them down. Each family kept handwritten collections that were passed down through the generations.

The first printed edition and, in fact, a collection of all oral and self-written tales of Jewish culture is the book "Maise-buch", which was published at the very beginning of the 17th century. The publisher, and possibly the collector of these works, was Yaakov ben Avraham Polak, who can hardly be called a Jewish storyteller. However, his work became a major event for Jewish literature of that time and fueled all Jewish fiction until the 18th century. It is impossible to determine who was the author of the tales described in the book and when they were written, but their source could be both Talmudic texts and midrashim, as well as medieval tales and legends overgrown with European folklore.

Maise-buch edition, 1602.

Carefully passed from mouth to mouth, many plots of fairy tales are so vital that they are relevant in the modern world. This book was translated into German in the 19th century and published in Hebrew in the 20th century. Unfortunately, the book was never translated into Russian, but many of the fairy tales included in it can be freely found in Russian.

In the period between the medieval editions of Jewish legends and the beginning of the flourishing of Jewish literature at the end of the 19th century, the fate of Jewish fairy tales was in the hands of the Hasidim and their students, who continued the Haggadic tradition and brought the stories unchanged until the century before last. Hasidic tales are a vivid example of Jewish literature. Velv and Rivka, The Rich Man's Mirror and others are all extremely expressive and witty. However, it is still not possible to single out the authorship of a certain person of a particular fairy tale, therefore, until the end of the nineteenth century, all written and retold fairy tales are considered folk tales.

Children's writers of the endXIX-early twentieth century

With the development of writing and science, the Jewish fairy tale ceases to be exclusively folk. The dispersal of Jews around the world does not interfere with the development of Jewish literature, including children's literature. The great Jewish writer, a classic of Jewish literature in Yiddish Yitzchok-Leybush Peretz also wrote fairy tales, but in an unusual verse format at that time. The Yitzchok-Leybush collection Stories and Tales, which was released shortly before the outbreak of World War II, made a valuable contribution to the genre of Jewish fairy tales and served as an inspiration for Jewish storytellers of the future.

Samuil Yakovlevich Marshak(1887-1964)

Another Jewish storyteller who brought Jewish legends out of the shadows and introduced the whole world to Jewish wisdom through his works was Samuil Yakovlevich Marshak. An interesting fact is that the surname "Marshak" is nothing more than an abbreviation for the Hebrew word "מהרש "ק " (Our teacher Rabbi Aaron Shmuel Kaidanover). And Samuil Yakovlevich belonged to the descendants of the great and wise rabbi and talmudist. It cannot be It is accidental that the writer was keenly worried about the spiritual component of Jewish traditions all his life, this explains the depth of the writer’s soul and the ability to subtly convey a capacious meaning in a couple of words.Marshak wrote poems on biblical themes, and in 1911 he even traveled to Eretz Israel and lived in a tent near Jerusalem. Spiritual craving for his culture was reflected in his children's works. According to the plots of his such sweet and simple fairy tales, the red line is respect and love for people, the equality of people of all races and shades. As in ancient times, a skilled storyteller, thanks to allegories , halftones and vivid examples, educates children's souls and instills high moral values.Marshak, with his work, brought the Jewish fairy tale to a new world new - level, because his books and collections were translated into many languages of the world and became part of the world classics.

Sasha Cherny (1880 - 1932)

A friend and ideological comrade of Samuil Marshak was another Jewish children's writer, a Ukrainian by origin - Sasha Cherny. He, like Marshak, wrote witty poems for children in an easy and slightly joking manner, just so that it would not be difficult for children to understand the simple truths that were contained in them. The life of the poet and writer was far from easy, he was not afraid to write works that were not censored, which is why at one time he was not accepted in society, and also created many problems for himself with the authorities and publishers. However, he left an impressive mark on Jewish children's literature, thanks to such tales as "Squirrel Sailor" and "Cat's Sanatorium", reflecting the prose of life of that time. Bright characters and colorful events are a hallmark of Alexander's work, and the content of the fairy tale is rather complicated, making these children's funny and ironic stories interesting for adults as well.

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky (1882-1969)

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky (real name Nikolai Vasilievich Korneichukov) was the illegitimate son of Emmanuil Solomonovich Levenson. His father did not recognize him, and this was a heavy burden in the soul of the writer all his life. However, this did not prevent Chukovsky from realizing his talent and becoming a bright star in the firmament of world literature, and Jewish literature in particular. He was not only a publicist, critic, translator and journalist, but also an unsurpassed author of children's fairy tales. His fairy tales are read with pleasure by parents to children today. "Aibolit", "Fly-Tsokotuha" and "Moydodyr" are fairy tales that have passed the test of time and become real classics of children's literature and carry a serious adult message, despite its allegorical form.

Shlomo Gilels (1873-1953) and Pinchevsky Mikhail Yakovlevich (1894-1955), who wrote children's novels and stories in Hebrew and Yiddish, are also worthy figures in the field of children's literature of the early twentieth century. These writers brought the genre of Jewish fairy tales to a new level, giving the content of fairy tales a Jewish color not only using the language, but also openly using Jewish traditions and culture in the repertoire. This was the beginning of the emergence of modern Jewish fairy tales from the shadow of other nationalities and getting rid of the veil of assimilation.

Jewish storytellers in the USSR

The work of Jewish storytellers on the territory of the Soviet Union had a tinge of the post-war period, the heroes of the plots reflected the Soviet ideal of morality, as required by censorship. But minor characters and plot twists often echoed the stories already known in the Agadic tradition. Looking back, we can say with accuracy that this was not an accidental, but even a well-thought-out move by the authors of children's literature of that time. A vivid example of this is the work of the children's writer and poetess of the mid-twentieth century Emma Efraimovna Moshkovskaya.

Emma Efraimovna Moshkovskaya (1926-1981)

At the very beginning of her formation as a writer, Emma Efraimovna received Marshak's approval, and released her first collection of poems "Uncle Shar", which simply breathes optimism and freshness. Each new verse teaches the child to love life and the people around, in simple forms tells about the rules of behavior and "what is good and what is bad." At the same time, it is especially valuable that the heroes of her poems and fairy tales show by their own example that you should never give up. Isn't that what many ancient Jewish tales based on the midrash and the Aggadic part of the Torah teach us?

The originality of her stories and poems resonated in the children's souls of that time and continues to occupy the minds of children today. And this is not surprising, because she expounded the plots of the works in a childish direct language, as if they were written by the child himself. Having chosen such an unpretentious childish language of presentation, Mashkovskaya did not at all abandon the deep meaning and capacious content of her works. A vivid example of her undoubted talent is the verse “And my mother will forgive me”:

I offended my mother

Now never ever

Let's not leave the house together

We will never go with her.

She won't wave out the window

And I don't wave to her

She won't say anything

And I won't tell her...

I take the bag by the shoulders,

I'll find a piece of bread,

Find me a stick stronger,

I'll go, go to the taiga!

I will follow the trail

I will look for pydy

And through the wild river

Build bridges go!

And I'll be the chief boss,

And if I'm with a beard,

And be always sad

And so silent...

And now it will be a winter evening,

And many years will pass,

And here's a jet plane

Mom will take the ticket.

And on my birthday

That plane will fly

And mom will come out of there,

And my mother will forgive me.

This short and simple work catches the eye of both children and their parents, because they describe the familiar feelings of each reader, revealing their new meaning. Based on the fairy tales of Mashkovskaya, cartoons that we loved were shot, songs were written to her poems, which meant universal recognition of the talent of the writer.

Noteworthy Jewish children's writers of the same era can be called Viktor Moiseevich Vozhdaev (1908-1978) and Yan Bzhekhov (1898-1966), who wrote serious and strict children's fairy tales, more strictly educating children in morality, responsibility and respect for others. Vozhdaev's tale "About Ivan Tsarevich and the Gray Wolf" is probably his most popular work among children. The story of how Prince the Firebird was looking for really excites the imagination and teaches readers perseverance and resourcefulness. The Polish poet and children's writer Jan Brzechow became famous thanks to his fairy tales "about Pan Klyaksu". The protagonist of these stories - Adam Neskladushka - is close to every child in many ways, which explains the success of these creations around the world.

Boris Vladimirovich Zakhoder (1918-2000)

Separately, it is worth mentioning Boris Vladimirovich Zakhoder, a children's writer, poet and screenwriter. He was born in Bessarabia, but lived most of his life in Russia. Zakhoder wrote in an original, very peculiar style that resonated with audiences, both children and adults. His stories contain fabulous prose, saturated with philosophy and lyrics. The most popular and interesting of his works were filmed, such as "The Whale and the Cat", "The Tale of the Good Rhino" and "Tari the Bird". These kind and bright cartoons still look easy and are quite relevant in modern society.

Rachel Baumvol (1914-2000)

A truly valuable quality of a children's author of fairy tales is his ability to attract and hold the attention of a child, and the Israeli storyteller Rachel Baumvol had such a talent. She was born in Odessa, but at the first opportunity she immigrated to Israel. The most successful fairy tales were written by her in the Soviet Union, such as The Checkered Goose, The Biggest Gift, The Friend in the Wallet. The heroes of these warm and instructive stories most often became forest animals, describing the originality of the Soviet era as an allegory. The writer instilled through her fairy tales in children kindness, mutual understanding and humanity - exactly those qualities that were the most valuable in people in the post-war period. For example, you can take an excerpt from her witty tale: "Why are you all cloves?" asked the orange girl. “So that you can share with everyone. “And why are you, an apple, without slices? So that I can eat you whole? No, the apple replied, so that you can give me wholly.. During her long career as a writer, Rachel has not retreated a single step from her self-determination as a Jewish writer. She defended her national identity and, until 1940, wrote exclusively in Hebrew. Not without reason, at the end of her career, critics called the writer "the keeper of the Jewish word." Despite the really difficult writing path, Baumville still remained true to her style of writing and uncompromising character.

Jewish storytellers of the 20th century

Outside the Soviet Union, the development of the Jewish fairy tale took place more freely. Writers scattered throughout Europe brought Jewish literature out of the shadows.

Leila Berg (1917-2012)

Leila Berg was one of the brightest writers of books for children, and at the same time an ardent defender of children's rights. She fully realized these two life vocations, and also left a valuable mark on children's literature. Her most popular fairy tales can be called short stories about a little car nicknamed "Kid", which tell children about the adventures of a kind and honest hero who easily and without compulsion goes through difficult situations, never losing heart. Another popular children's book of fairy tales by Leyla is Slice's Adventures. This book was intended for schoolchildren, because the example of its heroes reveals many complex moral and ethical questions, to which breeds even adults do not know the answer.

Leila Berg is rightfully considered one of the best children's writers of our time. Useful and informative for every child will be her series of stories "Spitz" and a book for very young "Steam Engine. Ducklings. Rybka”, which brought the writer The Eleanor Farjeon Award.

Miriam Jalan-Stekles (1900-1984)

The Israeli writer Miriam Yalan-Stekles possessed an original manner of presenting children's prose. Her last name is nothing but an acronym for her father's name, Yehuda Leib Nissan. This Israeli writer from childhood was familiar with Jewish traditions and Jewish culture, despite the fact that she was born in the Russian Empire. This is what influenced her style and manner of writing children's fairy tales, which are full of bright characters and captivate with haggadic plots. Her works “Life and Words” (Chaim Ve-Milim), “Paper Bridge” (Gesher Shel Niyar) and “Two Legends” (Shtei Agadot) amaze with the depth of their understanding of children's experiences and problems, as well as their philosophical meaning. Perhaps this is what made her works really popular in Israel and abroad, and the writer herself became the winner of the Israel Prize for Literature.

The Jewish people have always been rich in talented and successful world leaders. And children's literature is just one of the areas of their implementation. The versatility and depth of Jewish fairy tales has not been lost, despite the millennia of Jewish assimilation, and today every Jewish child can absorb the knowledge of his people through modern fairy tales and children's stories.

Would you like to receive the newsletter directly to your email?

Subscribe and we will send you the most interesting articles every week!

A recent Internet exchange of essays between Alexander Gordon and Alexander Barshai on the topic of whether Osip Mandelstam is a Jewish poet makes us think about the question: who, in principle, can be considered a Jewish poet, writer, cultural figure?

It is clear that the entry in the passport and even the presence of circumcision do not indicate belonging to the Jewish culture. When Joseph Kobzon deduced with his powerful baritone “Hello, Russian field, I am your thin spikelet,” he did not introduce Yan Frenkel’s song to the verses of Inna Goff into the bosom of Jewish culture.

I don't think you can refer to the language either. This will only complicate the problem. Now Russian is the native language of more than 20% of the Jews of the world. They read Maimonides in Russian, translated from Arabic, write books on Judaism, and I know one, Pinchas Polonsky, about the religious Zionism of Rav Kook, who was translated from Russian into Hebrew and introduced into the curriculum of schools in Israel. Today, far more Jews speak and read Russian than Yiddish. Further confusing the issue is that many Israeli Hasidic groups allow the use of Hebrew only for worship and study of sacred texts. And the language of Ancient Judea, Aramaic, is not used by modern Jews in everyday life at all.

It becomes incomprehensible why one of the dialects of German, Yiddish, which is spoken by fewer and fewer people, is Jewish, and Russian, which millions of Jews communicate, read and create religious and secular literature, is not Jewish.

It can be assumed that the reflection of the spiritual life of the Jews contemporary to the poet makes his poetry Jewish. Eduard Bagritsky in the poem "Origin" vividly described his departure from the tradition of the Jews, characteristic of many of his fellow contemporaries:

I don't remember which lodging

The itch of the coming life ran through me.

And childhood went on.

They dried it with unleavened bread.

They tried to trick him with a candle.

The tablets were pushed towards him point-blank -

Gates that cannot be opened.

Jewish peacocks on the upholstery

Jewish sour cream

Father's crutch and mother's cap -

Everything muttered to me:

- Scoundrel! Scoundrel!..

The poet concluded:

Outcast! Take your miserable belongings,

Curse and contempt! Leave!

Like most of the Jews of his generation, as the son of a rabbi - the "last prince in the dynasty" of Hasidic tzaddiks from Babel's Cavalry, Bagritsky went into the revolution. He owns the most beautiful revolutionary poem in Soviet poetry:

... Youth did not die,

youth is alive!

We were led by youth

On a saber hike

We were abandoned by youth

On the Kronstadt ice.

War horses

They took us away

On a wide area

They killed us.

But in feverish blood

We were rising

But the eyes are blind

We opened.

Arise Commonwealth

Crow with a fighter -

Be strong, courage

Steel and lead.

So that the earth is harsh

Has bled out

So that youth is new

Rising from the bones...

I never understood what kind of “commonwealth of a raven with a fighter” is: a raven on the corpse of a fighter or his victim?

Bagritsky glorified the Jew, who left the town for the responsible work of the commander of the food detachment, in his poem “The Thought about Opanas”:

...Along ravines and slopes

Kogan roars like a wolf,

Gets nose into the huts,

Which are cleaner!

Look left, look right

Snoring angrily:

"Shovel out of the ditch

Hidden Life!

Well, who will raise a storm -

Don't make noise, bro.

Mustache in the garbage heap,

Shoot - and cover!

No wonder that "like a quail in life, Kogan was caught." At the execution, the commander of the food detachment behaved well. Still, the dream of the poet is surprising:

So let me die

At Popov's log

The same glorious end

Like Joseph Kogan! ..

A significant coincidence: in the same 1926, Mayakovsky came up with the same end for himself in the poem “To Comrade Nette ...”: “I want to meet my death hour the way Comrade Nette met death.”

It was a culture of death and worship of it. In the main revolutionary song, the Bolsheviks sang their fate: "We will boldly go into battle for the power of the Soviets and, as one, we will die in the struggle for it." They will die "for this" in 1937. The revolutionary ecstasy of Bagritsky, cited above, is taken from a poem with the appropriate title "Death of a Pioneer". Yes, and Mayakovsky, having written the poem “Good!”, Shot himself. Bagritsky was lucky: he died a natural death at the age of 38 in 1934. His wife was arrested in 1937. In Karaganda, she went every day to check in at the NKVD office on Bagritsky Street ...

A colorful poem about the departure of Jews from the ghetto to the "new life" - "The Tale of the Red Motel, Mr. Inspector, Rabbi Isaiah and Commissioner Bloch" - was written by Joseph Utkin.

Under Tsar Motel, "I thought to study in a cheder, but they made me a tailor." However, "on Fridays Motele davnel, and on Saturdays he ate fish." The Chisinau pogroms came: "Only ... Two ... Pogroms ... And Motele became an orphan." But then the revolution arrived in time: "Motel shaved the sidelocks, took off the lapserdak." He made a career: “Here is Motele - he is “from” and “to” sitting in an angry office. Sits like the first person. Well, of course, "and Motele will not leave, and even to America."

However, sing "Comrade Utkin", as Mayakovsky called the poet in his verse, Motel not in 1925, but in 1937, he would surely regret that he did not hit the road in America in a timely manner.

A kind word for the shtetl in pre-war Jewish literature was found in Vasily Grossman's story "In the City of Berdichev". In it, the world of the commissar, who failed to exterminate the child and has to give birth, and the world of the Jewish worker Magazan, the caring father of a large family, collide. "Comrade Vavilova" leaves the newborn to the Jews and goes on to kill enemies. The contrast between Jewish philanthropic morality and the new communist author had to be softened, at least he succeeded in emphasizing, with an absurd conclusion: “The shopkeeper, looking after her (the commissar), said: “These are the people who were once in the Bund. These are real people, Bala. Are we people? We are manure.”

No matter how the artists treated the world of the shtetl - with love for its humanity, like Grossman, or rejecting it, like Bagritsky and Utkin - this world was doomed. Part of this world emigrated to America at the beginning of the 20th century and transformed into the Yankees, another went up to Palestine to recreate Israel, and a third went to Soviet cities. The rest were killed by Hitler.

Bard Alexander Gorodnitsky created a poetic film in memory of the world of shtetls "In Search of Yiddish". In other places that raised world-class geniuses at the beginning of the century, Gorodnitsky could find only one person who understood Yiddish. And that is a non-Jew. “If the language died, then the people who spoke it probably also died?” the bard asked.

The situation is paradoxical: the poems of Jewish Yiddish poets killed by Stalin on August 12, 1952, the property of Jewish culture, have sunk into obscurity. Jews who read poetry in the mass do not know Yiddish, and Hasidim who know Yiddish do not read the poetry of secular poets. The books of the most famous Yiddish writer of the 20th century, the Nobel laureate Bashevis-Singer, are popular - but in translations into English, Russian, and Hebrew.

However, the people who spoke Yiddish at the beginning of the 20th century and its culture did not die. Their fate was remarkably explained by Mandelstam in the essay "Mikhoels" to which Gordon refers: plasticity of the ghetto, about the enormous artistic force that survives its destruction and finally blossoms only when the ghetto is destroyed.

I do not agree with the way Gordon understands this idea: that "the isolation of the people will stop, and it will dissolve in the surrounding culture." The Jews went through many cultures, accepted and forgot different languages, and now in Israel they have returned to the one in which they communicated with the Almighty in the desert more than 33 centuries ago. Jews wrote poetry in all these languages. Thanks to the “plastic basis and strength of Jewry,” which made it possible to “transfer through the centuries a sense of form and movement,” about which Mandelstam wrote, the Jews developed their own culture in a new world for them, enriching both local for them at that moment and world culture. Thus, the great American literature of the 20th century is to a large extent Jewish literature in English. And the books of Bellow, Malamud, Doctorow and others illustrate Mandelstam's idea that "the Jew will never and nowhere cease to be brittle porcelain, never throw off the finest and spiritualized lapserdak."

Therefore, Gordon's statement seems unfair to me: “Osip Mandelstam is a great Russian poet ... Mandelstam did not need the Jewish people. The Jewish people as such do not need the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, artificially attached to it as a national poet, whose work did not contribute to the culture of the Jewish people. You can't "artificially" attach a poet to the people as nationals. To do this, he must express the quintessence of the people, or at least part of it. And Mandelstam expresses it.

It seems to me that Mandelstam is not a Russian poet at all. In it, I do not see any Russianness - neither in themes, nor in the worldview. And it can be made Christian only by forcibly adding to it, as Gordon does, Pasternak - a truly Russian and Christian poet. Morally preparing for the feat of publishing Doctor Zhivago, Pasternak in the verse “Hamlet” simply spoke with the words of Jesus from the Gospel: “If only it is possible, Abba Father, // Carry this cup past.” So after all, Boris Leonidovich was not cunning when, in the famous telephone conversation with Stalin regarding the arrested Mandelstam, in the version of this conversation retold by the poet to Sir Isaiah Berlin, he said “that as poets they are completely different, that he appreciates Mandelstam’s poetry. But he does not feel inner closeness with her.

And indeed, Pasternak was a patriot of Russia and the Soviet Union, dedicated the poems “High Illness”, “Nine Hundred and Fifth Year”, “Lieutenant Schmidt” to the revolution. Sir Berlin reasoned: “Pasternak was a Russian patriot - he had a very deep awareness of his own historical connection with his country ... This passionate, almost obsessive desire to be considered a real Russian writer, with deep roots in Russian soil, was especially noticeable in negative feelings for his own Jewish origin. Admiration was also involved in Pasternak's attitude towards Stalin.

In Mandelstam's heroic verse, the feeling of his greatest disgust towards the tyrant is brilliantly expressed:

His thick fingers

like worms, fat,

And the words, like pood weights, are true,

Cockroaches are laughing mustaches,

And his bootlegs shine.

This poem, in addition to Jewish rebellion and adventurism - Mandelstam was not a suicide, but risked that there would not be an informer among the people to whom he read the poem - it is also a sign of the poet's cosmopolitanism. The Bolsheviks at the trials of 1937 agreed with slander on themselves, because they believed that with their humility they were serving the interests of the USSR. These interests, as Bukharin explained shortly before his arrest to Boris Souvarine, in anticipation of his arrest, are symbolized by the figure of Stalin. For Mandelstam, these interests, and Stalin, and the country that he symbolized, were disgusting.

And the damn walls are thin,

And nowhere else to run

And I'm like a fool on a comb

Someone has to play.

Insolent Komsomol cell

And the university song is fighting,

Sitting on the school bench

Learn to twitter executioners.

And instead of Hypocrene's key

Long-standing fear jet

Breaks into hacky walls

Moscow evil housing.

The key of Hippocrene is also important here (so, with two "p", Pushkin wrote). The world for Mandelstam is not Russia (especially the Soviet one). His hymn to cosmopolitanism is intoxicating:

I drink to war asters, to everything

what they reproached me with

For a master's coat, for asthma,

for the bile of a Petersburg day.

To the music of the Savoy pines,

fields of Champs Elysees gasoline,

For roses in the cockpit of a Rolls-Royce

for the oil of Parisian paintings.

I drink to the waves of Biscay

for the cream of the Alpine jug,

For the red arrogance of the English women

and distant colonies of quinine...

About the same in another poem:

I pray like pity and mercy

France, your land

and honeysuckle

The truth of your doves

and false dwarfs

Vine growers in their barns

gauze.

I have not heard the stories of Ossian,

Haven't tried old wine;

Why do I see a clearing,

Scotland's blood moon?

In the same row, and "To the German Speech", and his Italy, and especially Ancient Greece.

Stalin was right: Jews in the majority are a nation of cosmopolitans. At least they were before the re-establishment of Israel. Cross the globe from Manitoba to Australia and from Birobidzhan to Chile and you will find Jewish communities everywhere. And if they are not there somewhere, it is because we were expelled from there.

And what about Jewish culture? Thanks to the “plastic basis and strength of Jewry,” which Mandelstam wrote about, we are renewing our culture in a new place.

"POETS-BAPTIZED JEWS"

Election ghetto! Shaft and ditch.

Please don't wait!

In this most Christian of worlds

Poets are Jews!

(Marina Tsvetaeva)

Self-awareness of the personal, national and universal is most strongly manifested in the poetic word. The dispersal of Jews in many countries and continents was the reason that many Jewish poets created their works in different languages of the world. Hebrew literature has existed for the 33rd century. A noticeable trace was left by Jewish poetry in Spanish and Arabic in the years of the early Middle Ages, and in the last 2 centuries - in European languages. A little over a century ago, Jews entered Russian poetry and immediately occupied leading positions in it: Sasha Cherny, Mandelstam, Pasternak, Galich, Korzhavin. The list of Jewish surnames could be continued, but I will confine myself to these names - they are the ones that link the articles: about baptized Jews in Russian poetry. They were all baptized.

Brodsky's name remained outside this list, since publications and speeches by people close to the poet emphasized that he had never been baptized. For example, Ilya Kutik said: "Brodsky was neither a Jew nor a Christian, he wanted to be a Calvinist ...". By the will of Brodsky's wife, a cross was erected on his grave. It cannot be ruled out that the poet foresaw this possibility by writing the poem “I erected a different monument to myself.”

The question of the baptism of prominent poets is confusing to many people. Why did these respected, talented and close by blood people leave their roots, make themselves Russians “just like that”, without formally renouncing their Jewishness? Some of them didn't even change their last names.

Russian poetry of the 19th century was simple, accessible, musical and easily perceived. But in the poetic allegory of the poets of the 20th century, sometimes even venerable writers do not always understand the meaning of the creations of their colleagues.

So Brodsky asked Nadezhda Mandelstam to comment on one of her husband's poems. But she could not give him a transcript.

"Tsvetaeva's poems are sometimes difficult, they require a thoughtful unraveling of her thoughts," wrote Anastasia Tsvetaeva. Understanding the allegories of the poetess is not always available not only to ordinary lovers of poetry, but also to those for whom the study of Tsvetaeva's work has become a profession. For example, critic V. Losskaya believes that the words of the poetess often "affect all the confusion of her (Tsvetaeva) emotional reactions."

The lines from Marina Tsvetaeva's "Poem of the End" are very famous and often quoted:

S. Rassadin comments as follows: “After all, the ghetto of chosen ones, and not exiles, is such a ghetto, complaining about being in which is just as pointless (and would you even want to?) How to ask G-d to save you from the gift sent down to him ... “Jew” in the very sense in which the Slav woman Tsvetaeva applied the word to herself and her kind.

Two years after the creation of The Poem of the End, Tsvetaeva wrote in one letter: I love Jews more than Russians and maybe I would be very happy to be married to a Jew, but - what to do - I didn’t have to.

Alexander Mikhailovich Glikberg - Sasha Cherny wrote about himself: “The son of a pharmacist. Jew. Baptized by a ten-year-old father to be assigned to a gymnasium. He passed the exam, he was not accepted because of the percentage rate. The father decided to baptize him. That's the whole involvement of Sasha Cherny in Christianity.

The poet was born into a wealthy but uncultured Jewish family. Mother - a hysterical woman and a cruel, stingy father created an intolerable situation in the family. Following his brother, Sasha ran away from home. He was then 15 years old. His further life was spent in a world far from religion.

Sasha Cherny is a satirist poet. His sharp pen stung not only the king and politicians, for which he was arrested and brought to trial. The “Russian layman” and the “true Russian Jew” suffered no less. The poet was especially merciless towards the anti-Semites, who live under the slogan: "Jews and Jews, chickens and sidelocks. Save Russia, sharpen your knives!" (Judophobes). The following lines of Sasha Cherny are interesting: “But what is a Jewish question for Jews. \ Such a shame, a curse and a rout, \ That I dare not touch him \ With my poisoned pen. I could not find deep Christian motives in the poet's work.

Mandelstam, like Heine, wanted to unite Judaism with Hellenism, and also painfully and forcibly came to Christianity. He betrayed the faith of the fathers, but, as it were, not completely. The poet did not go to the Orthodox Church, but chose the Protestant church in Vyborg. He was not baptized with water.

Having converted to Christianity, he never renounced his origin and the title of Jewry, which he was always proud of. The “memory of blood” was peculiar to Mandelstam. It went back to the biblical kings and shepherds when there was no Christianity, and the later period, when Christianity won, according to S. Rasadin, he completely forgot.

In the Stalin period, Mandelstam began to be afraid of the totalitarian power of monotheism, and consoled himself with the fact that the Christian doctrine of the trinity was more suitable for his suffering nature. Mandelstam, said Nadezhda Yakovlevna, "was afraid of the Old Testament god and his formidable totalitarian power." He said that by the doctrine of the trinity, Christianity overcame the sovereignty of the Jewish God. "Naturally, we were afraid of autocracy." This statement, according to some critics, can be interpreted as Mandelstam's commitment to Christianity.

What kind of a Christian is he if he had no desire for martyrdom? All his life, Mandelstam lived in need and suffered greatly from this, not at all in a Christian way.

Mandelstam's attitude towards Jewry was complex and contradictory. He recalled the constant shame of a child from an assimilated Jewish family for his Jewishness, for importunate hypocrisy in the performance of a Jewish ritual, for "Jewish chaos" (... not a homeland, not a home, not a hearth, namely chaos).

In the 1920s, Mandelstam's life was spent in throwing between Christianity (" now every civilized person is a Christian") and Judaism ( "What a pain ... for a strange tribe to collect night herbs"). Later, he admires the "internal plasticity of the ghetto", notes the melody and beauty of the Yiddish language, the logical balance of Hebrew.

In The Fourth Prose, he said: "I insist that writing, as it has developed in Europe and especially in Russia, is incompatible with the honorary title of a Jew, which I am proud of."

The most restless of all Russian poets, Osip Mandelstam was still lucky in one thing: he found a woman keeper. Nadezhda, nee Khazina, was also a Jewess, baptized in childhood. She survived the poet for 42 years and dedicated her life to the cause of perpetuating the memory of the poet. The book "Memoirs" brought Nadezhda Mandelstam world fame.

In 1936, Pasternak was stigmatized for the lines "I rubbed myself into someone else's relatives."

Trying to somehow efface his Jewish "guilt", the poet was too carried away by the Russian principle in his work, that he even crossed the boundaries of what was permitted: in 1943 A. Fadeev accused Pasternak of great-power chauvinism.

The poet did not hide this: “I have Jewish blood, but there is nothing more alien to me than Jewish nationalism. It can only be Great Russian chauvinism. In this matter, I stand for complete Jewish assimilation...”.

After Doctor Zhivago appeared in Europe, the world Jewish community condemned the poet for so-called intelligent anti-Semitism and apostasy. Upon learning of this, according to Ivinskaya, "Borya laughed: - Nothing, I am above nationality." And Tsvetaeva said: from some point of view and Heine and Pasternak are not Jews ...

Nothing is known for certain about Pasternak's baptism. The poet once admitted in a letter to Jacqueline de Proire that he "was baptized in infancy by my nurse ... This caused some complications, and this fact has always remained an intimate semi-secret, the subject of rare and exceptional inspiration, and not a quiet habit." Did it take place due to the arbitrariness of some nanny in secret from the whole family?! It will probably never be known whether such an event was real or a far-fetched, artistic image created by the poet's imagination. However, when entering the Faculty of Philosophy of Margburg University, B. Pasternak, answering questions about religion, wrote down: "Jewish."

Pasternak advised Ivinskaya to write down about his passport data: “Mixed nationality, write it down.” The beloved woman wanted to present Pasternak as a purely Russian poet. In the chapter “Questionnaire” from the book of memoirs “Captured by Time”, Olga Ivinskaya told about the poet: “Baptized in the second generation, a Jew by nationality, B.L. (Boris Leonidovich) was a supporter of assimilation.” This is only half true. His father, Leon Pasternak, "remained a Jew until the end of his days."

In Pasternak's many-sided work there is not a single line about the catastrophe of European Jewry. But in the work of Naum Korzhavin, many pages are devoted to this topic. He wrote about Babi Yar, about "the world of Jewish shtetls..., synagogues and gravestones", about his Orthodox grandfather, about the fate of a Jewish immigrant, about various aspects of Jewish self-perception.

Galich sincerely supported the doctrine of the assimilation of Soviet Jewry. “I, a Russian poet, cannot be excommunicated from this Russia by the “fifth point.” His drama "Sailor's Silence", which in fact proclaimed assimilation, was originally called "My Big Land". With these words of the Jew David, the play ended. Theatrical ideologists demanded to change the name.

Heinrich Böhl noted that creative people in totalitarian countries seek a way out in religion, while in democratic countries they become atheists.

Maybe this is the reason for the baptism of Galich and Korzhavin?

They had one godfather, also from Jews - Alexander Men, a man of great talent and charm. Unfortunately, there was no such brilliant preacher among Russian Jewry.

I learned about the apostasy of Galich and Korzhavin quite recently, upon my arrival in America. I have not excluded them from the circle of poets, to whom I often return and re-read. But the question is, "Why Christianity?" - remained. If for Sasha Cherny and Mandelstam baptism was a necessary measure, then for Pasternak, Galich and Korzhavin Christianity became a conscious act and a spiritual need. Korzhavin even now says that a Russian poet can only be a Christian.

It is well known that "a poet in Russia is more than a poet" - he is a god, or at least a prophet. In the Russian world, a Jew is traditionally a foreign element, an enemy, and only a conversion to Christianity will allow him to take the place appropriate to his talent. Such a judgment exists, but I do not see it as convincing.

Great poets knew Russian proverbs well: “Change faith - change conscience”; “Baptize a Jew and lower it under water”; "A forgiven thief, a healed horse and a baptized Jew have one price."

In the great and powerful language, the word "apostate" is synonymous with "renegade", which in the Russian mentality has a disparaging connotation.

Pasternak, Galich and Korzhavin knew that because of Christianity there are currently 100 million Jews missing on the globe. It was no secret for them that one of the greatest poets of all times and peoples, Heinrich Heine, admitted after baptism: “I wish all renegades a mood similar to mine ..., I left behind the crows and did not stick to the peahens.”

Surely baptized poets read the lines of B. Slutsky:

Orthodoxy is not in prosperity:

during the most recent years

it makes up food

except for baptized Jews.

I.Akselrod

Jewish World (New York)

are our favorite classics. Only here in the world of children's literature there are many more excellent writers and poets with Jewish roots than we used to think. Books of which authors, in addition to those already mentioned, can be put on the children's shelf? Literary reviewer Lisa Birger shared her favorite books, and JewishNews added a few of her own.

Valerie Nisimov Petrov "White Fairy Tale"

Who: Bulgarian translator Valerie Nisimov Petrov (Mevorakh) was born to a lawyer who became Bulgaria's UN representative and a French teacher. Despite his Jewish origins, he was brought up in the Protestant faith, which his parents converted to when he was just a child. Literary talent in the boy woke up early - already at the age of 15 he published his first poem "Birds to the North". He received an education not literary, but medical, and even led a medical practice. But the word won over the scalpel.

After the end of World War II, Valerie was appointed press and cultural attache of the Bulgarian embassy in Italy, and in 1945-1962 he was deputy editor-in-chief of the satirical magazine Shershen. Petrov wrote his own books and translated others - thanks to him, the works of Rudyard Kipling and Gianni Rodari sounded in Bulgarian. Valerie never forgot about his Jewish origin - and even transferred this love to creativity: among his works there is a book "Jewish Jokes".

Why read: The book for children 4-5 years old "White Fairy Tale" with wonderful illustrations (there are two versions of the design, and both are magical) tells about "how the animals live in the winter forest." This amazing kind tale was told to one small and very curious deer by a meteorologist who watched the instruments in the mountains. A fascinating story begins with a song about friendship: Not by chance and not suddenly / They say - “the first friend.” / For the first for the sake of a friend / He is ready to go into the fire, / If a friend is in trouble. / Stretch out your hand to him. / Call - and right away he, / Without saying extra words, / For the sake of a friend, he will shed blood. / “First friend” - it doesn’t sound in vain!

Lev Kvitko "Visiting"

Who: An amazing poet of an amazing fate, Lev Kvitko, was born at the end of the 19th century in the town of Goloskov, Podolsk province (Khmelnitsky region). He was orphaned early, remained in the care of his grandmother, studied a little in a cheder and started working as a child.

The first works that Lev wrote in Yiddish appeared in print when he was not even 15. From the middle of 1921, Kvitko, who accepted the ideals of communism, lived and published in Berlin, then moved to Hamburg - there he was an employee of the Soviet trade representative and continued be printed. But, as usual, once they saw an enemy in him. He was not allowed to go to the front, because it was considered that in Germany he carried out subversive activities for the Soviet government, and he was friends with the wrong people. But he was allowed to become a member of the Presidium of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) and the editorial board of the JAC newspaper Einikait. And although Kvitko was allowed to express himself in the public arena, he was already doomed - in early 1949 he was arrested among the leading figures of the JAC, accused of treason, and in 1952 he was shot.

Why read: Lev Kvitko wrote lyrics for children, and all of his poems were in Yiddish. It was translated by Marshak, Mikhalkov, Blaginina and Svetlov, and one of these collections was the wonderful "Visiting". For many, these poems are associated precisely with the names of their translators, but the author, Kvitko, remained a little in the background. “Have you heard about kitty - about my dear / Mom does not like kitty, but I love her! / She is so black, and her paws are like snow, / Well, she is smarter than everyone else, and more fun than everyone!”, “Anna-Vanna, our detachment / Wants to see piglets! / We won’t offend them: / We’ll have a look and go out! - these and many other lines familiar from childhood can be seen in the collection "Visiting". And the illustrations for the collection, especially in the 1962 edition, are pure art in and of themselves.

What else to read: The story "Lyam and Petrik", one of the earliest works of Kvitko. It was written in 1929. The writer considered it unfinished and was going to finish it, but did not have time. This work is largely autobiographical - the story of the little Jewish boy Lyam echoes the poet's childhood and describes in the background the pre-revolutionary and revolutionary years in Ukraine at the beginning of the last century.

Hans and Margaret Ray "Curious George"

Who: One of the first successful writing duos with a remarkable background: Jews from Germany who met in Brazil, lived in Paris since 1935, and fled the Germans hours before they arrived in Paris on bicycles made from spare parts. According to legend (sometimes a legend is so good that you don’t even want to refute it), practically the only thing they managed to take with them when they ran away from Paris was the manuscript of “Curious George” - as soon as the couple got to New York, the manuscript ended up in publishing house and eventually became one of the most successful book projects of the century.

Why read: Curious George is a little monkey who is caught in Africa by the man in the yellow hat and brought to America for a happy life at the zoo. I must say, George has no doubt that his life at the zoo will be happy, but he simply does not want to stop there. He is the first and chief at the festival of disobedience, which in the middle of the last century was the main form of resistance to all the horrors of the time. But today this book is no less loved by children and understandable to them: in the end, it is about absolute freedom, which adults unsuccessfully try to restrain, and by the way - about absolute love.

What else to read: “Stars. New outlines of old constellations. A 1954 book in which the star chart and constellation images look clearer than in a school astronomy course. It is not surprising that it is still being republished and has recently been released in Russian in an updated translation: in 1969, when the book was first published in the USSR, our ideas about space have changed a little, but still.

Maurice Sendak "Where the Monsters Dwell"

Who: Artist Maurice Sendak has devoted his entire life to children's books — and although his golden canon includes only four or five books, he is quite rightly considered one of the main children's authors of the last century. Born into a family of Jewish emigrants from Eastern Europe, instead of bedtime stories as a child, Sendak heard stories about his cousins who died in the Holocaust - and is it any wonder that his art ended up being very specific. But most importantly, he was and until the end remained completely unlike anyone else. His children are hooligans, jumping naked, dressing up as monsters, and adults, having grown huge claws and staring huge eyes, try to eat them. The incredible popularity of Sendak's books - a whole new generation of our cultural heroes grew up on his books - proves that he really understood children better than all adults.

Why read: "Where the Monsters Live" - the only one of Sendak's main books translated with us - the story of the boy Max, who made a big shurum-burum at home, and when his mother sent him to his room to sleep without dinner, a whole a new world and Max went across the ocean to visit the country of monsters. Sendak is a real great artist, the world of monsters is so coolly rethought here and presented that no matter what time you read it, and the journey to the country of monsters again turns out to be a strong experience. Including therapeutic - reading this book with a child, as if you are going through that most difficult part of a child's game with him, when it is not clear who exactly turns into a real monster: a child or his angry mother. By the end of the book, both can feel like ordinary, slightly tired people again.

What else to read: Elsie Homeland Minarik "Teddy Bear". Artist Maurice Sendak. The first - even before "Monsters" - Sendak's artistic success, chamber and incredibly tender stories about the Bear cub and his mother in an apron - also an American classic.

Eric Karl "The Very Hungry Caterpillar"

Who: The world's top toddler author, period. The greatness of Eric Carl hardly needs proof, but know, for example, that he even has a lifetime museum in Massachusetts, which is deservedly considered the American children's picture book center with excellent exhibitions and educational projects. Generations of adults have grown up on Eric Carle's books, and in recent years, his favorite works like The Very Hungry Caterpillar and Bear, Brown Bear, Who's Ahead have been celebrating their fiftieth anniversary in recent years. What can I add - a long summer.

Why read: Eric Carl in many ways anticipated the modern concern of parents with early education of children, his books are always not just colorful, but teach a lot at the same time. According to “Bear, brown bear, who is there in front”, the child learns the colors and names of animals, according to “The speckled rude woman” learns to tell the time and compare sizes, and books like “The Blue Horse” in a generally revolutionary way for a cardboard book help to learn how to breed different types of fish: a "pregnant" seahorse swims in the sea, communicating with other fathers about their offspring. Fiction! And, of course, where without the “Very Hungry Caterpillar” - there is both counting and fine motor skills (the book must be read with a cord, play “caterpillar” with it and thread it through the holes, eat apples and plums with the heroine of this book ), and the first acquaintance with the wonders of nature in the form of a magical transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly in the finale.

Shel Silverstein "The Generous Tree"

Who: An American poet, cartoonist, musician, and generally a man of many versatile talents - among other things, he covered "Hamlet" in rap, traveled around the world on behalf of Playboy magazine, collecting his travel notes and drawings in a collection of travelogue cartoons, and drew a cartoon himself according to The Generous Tree Legend has it that he was dragged into a children's book by Ursula Nordström, the legendary genius editor to whom America literally owes its children's literature. Silverstein himself said that he was persuaded by another great children's illustrator, the Swiss Tomi Ungerer. One thing is for sure: his parable books, and above all, of course, The Generous Tree, were published in millions of copies and became absolute world classics.

Why read: “The Generous Tree,” a story about an apple tree that gave all of itself to a little boy, and gave more and more until it gave all of itself, can be read like a thousand different stories: about sacrifice, about motherly love, about Christian love etc. And to see here thousands of different answers: to be indignant, to sympathize, to be indignant. Such an endless exercise in reading and understanding, valuable in itself. And two words about the illustrations: although all over the world Silverstein is read only in his own, slightly naive, pencil version, he was first translated into Russian in the 80s with pictures by Viktor Pivovarov. Pivovarov's reading of the tale turned out to be a little brighter than that of Silverstein himself. There is a harmony here that is not at all obvious in the original edition, and his illustrations themselves (which arose, as always, because no one in the Soviet Union thought to respect copyright) are a real rarity today.

What else to read: Silverstein's books Rhino For Sale or One and a Half Giraffe are nothing like The Generous Tree, it's an exciting, fast-paced, rather nonsensical and very fun rhyming game. And he himself called his favorite book “Lafcadio, or the Lion who shot back” - about a lion who knew how to shoot, and from the jungle went straight to the circus arena, became a superstar, almost humanized, but did not find happiness.

What do you want to endlessly talk about with the editor-in-chief of the Lechaim magazine and the Knizhniki publishing house? Of course, about literature!

How to make Jewish culture and literature attractive to non-Jews?

I think the question is a bit late. Jewish culture in general and literature in particular is incredibly popular today and is part of European and world culture. Here the main question is what to call Jewish culture.

If we consider cuisine as such, for example, then we should not expect that people of the 21st century will eat stuffed neck, which is the product of a very poor cuisine. If we are talking about Jewish music, then it is worth remembering the huge jump in popularity of klezmer music in different countries, from Japan to Finland. At the same time, in most countries where klezmer is popular today, there are practically no Jews. When we talk about American literature, we think of Philip Roth, who deals with Jewish themes in almost all of his writings. That is why he is a representative of not only American or world, but also Jewish culture.

If we are talking about traditional Jewish literature, then I, as a publisher, can say that for us the unprecedented interest in our books was completely unexpected. Not only to popular literature, but also to sacred, classic books that do not correspond to new-age. However, the main buyers of our books are non-Jews.

Therefore, the question is not whether this can be done, but how to maintain this interest and not spoil the impression. It is necessary to do it qualitatively, to use the developments that exist in world culture. If we are talking about music, then this music should be well written and recorded. Speaking about exhibitions, these museums should exist according to the principles of modern museology. It is necessary to fit an interesting Jewish culture into the world context.

The Jewish Museum in Moscow gained its popularity due to modernity?

Undoubtedly. Our main task was to pack things that are interesting and important to us in forms that correspond to the latest museology. You cannot make a modern information museum (and this is exactly what our museum was intended to be) based on the technology of the 19th century. In our opinion, most of the Jewish museums in the world are lagging behind in this respect.

Jewish museums, which are not far behind in this regard, are among the best museum institutions in the world. Not in the Jewish world, but in general. I'm talking about the Polin Museum in Warsaw, the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the Holocaust Museum in Washington, Yad Vashem. Our museum is the most technologically advanced in Eastern Europe, apart from our main friends and competitors, Polin. For us, not only the forms of presenting information and the knowledge that we want to convey are important. We think about technology, about accessibility and understandability for a modern person.

By what criteria should we, as Jews, choose those parts of the culture that we want to show the world? Or is it enough that it's just not a sham?

Kitsch as such is a common problem. This also applies to cinema, and literature, and fine arts. The world likes to use incredibly simplistic language when talking about many topics. Roughly speaking, Russia is a nesting doll, and Jews are "Hava Nagila". Unfortunately, this kitsch, which is the result of an increased interest in Jewish culture, is being used to the maximum. This also applies to the so-called Jewish humor, and Jewish music, and the theme of the Holocaust. No matter what topic we're talking about, there will be kitsch. It is the result of interest.

Kitsch topics can be talked about at the highest level, but even the most serious topics can be easily made into popular material. I wouldn't choose anything, it's more about the ways and depth of the discourse.

The wonderful translator and writer Asar Eppel called the people who do what you are talking about "the havana-killers of Jewish culture." This song is a wonderful symbol of all this, but we have no doubt that we can talk about it seriously. We need to try to take the most popular topics from kitsch and present them at a higher level. But you need to be prepared for the fact that something that has become popular will at some stage become the subject of kitsch. This is completely normal, this is how culture exists and there is no point in fighting it.

The Lechaim magazine turns 25 this year, the Knizhniki celebrates its 8th. They popularized Jewish literature in the Russian-speaking environment. Will this popularization influence the emergence of young Russian-speaking Jewish writers?

This is quite a sore subject. Literature is a reflection of life. Why is there a huge amount of Jewish literature in America? Because American Jewish life is not "American Jewish life," but "American Jewish life," even forty years ago. Therefore, there are Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, who grew up in Jewish themes, whether they like it or not. Roth devoted most of his life to trying to prove that he was not a Jewish writer. In my opinion, he did nothing. Accordingly, for the emergence of serious Russian-language Jewish literature, a serious layer of people must appear for whom Russian Jewish life does not exist through a comma.

There is a very good new wave of young Jewish writers - these are emigrants who were taken away from different cities of the former Soviet Union. They grew up in Canada or America and describe the experience of a Russian-Jewish-American young man. Suffice it to recall such names as David Bezmozgis, Harry Steingart and so on. This theme is exploited by young American writers such as Foer, for example.

As for us, our aspens, it seems to me that the physical mass of people who live such a life does not yet exist. There are sprouts of Russian-Jewish literature, there is Yakov Shekhter and his brother David, who thirty years ago wrote a book about the underground Jewish life in Odessa in the seventies. There are young guys who write similar stories. I would single out a wonderful writer, Inna Lesovaya from Kiev. The fact that it is little known to a general audience says a lot about the general reader. It cannot be said that this literature does not exist - there is simply very little of it, in America there is much more. But more precisely because literature is a reflection of life.

Writers appear where Jewishness is not a choice, but is dictated by life around. A person who chooses to be Jewish often renounces a past life. Literary people who have come to Judaism, as a rule, cease to engage in literary work.

In America and Israel, there are writers who grew up in orthodox families. They have something to write about, their works come out of their veins. All that remains for these authors is to get a tool and describe what they lived. This is similar to the process of Russian-Jewish literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when great writers emerged from a very Jewish milieu. We need a Jewish world, which does not exist at the moment.

How realistic is the appearance of this world in our latitudes?

I'm not a big optimist. This is still a very washed out part of society, people leave and begin to live in other languages. Also, I don't see organic. There is some layer, a large number of people have appeared who study Judaica and live by it. These are people of a fairly wide range, among them there are potential writers. It's hard to say if anything will come of them. But, again, these people are not enough for the critical mass needed to guarantee the emergence of writers.

Hundreds of thousands of people grew up in the Jewish neighborhoods of New York or Boston. Of these hundreds of thousands, we received a dozen important names. The probability of the appearance of big names from the organic Jewish environment of people left to live in the countries of the former Soviet Union seems to me low.

This is not an easy question. The outstanding translator and researcher Shimon Markish devoted an entire book to this issue. In many ways, it was he who determined our attitude to this. Our publishing house has a large series of "Prose of Jewish Life", within which more than 150 volumes have already been published. This is the largest Russian-language series, and not only among Jewish books. Our principle is very simple - the book should be the prose of Jewish life, it should describe the life of Jews.

To what extent is this Jewish life Jewish? I think it is. A Jew in the Diaspora is always not only a citizen of his country, but also a Jew. This can be called "self-reliance". It is this "self-standing" that automatically gives the pain point that you are talking about. He doesn't think about it, he writes like this.

I recently read an interview with actress Rachel Weisz in Time magazine. She starred in Denial, a film about Deborah Lipstadt's trial against a Holocaust revisionist. In an interview, Rachel notices that Deborah speaks special Boston Hebrew. She is asked what this Hebrew language is, to which she replies that it is a Talmudic accent, a question mark at the end of each phrase.

Deborah Lipstadt may be an American intellectual, she may reign supreme, she may be a great connoisseur of American discourse, but she will still have that question mark at the end. It's part of her mentality. How did this mentality become her mentality? I doubt it's genetics, it smells of racism. But the acquisition of this feature from the environment seems to me more likely. From friends, from relatives, from parents. American Jewish liberal discourse is always very Jewish in its essence, if you read it. Deborah's place could be Cynthia Ozick, anyone, but there will be a question mark. I don't know if young Americans have it. I think it will wash out.

To what extent is Doctor Zhivago a Jewish novel? As much as Pasternak is a Jew. It seems to me that Pasternak's thrashings and rather anti-Semitic passages in this novel are quite Jewish in their essence. They are the very “pain point”. If this book were written by a non-Jew, then I would say that it is anti-Jewish. A normal person who does not reflect on this topic will not dwell on the fact that Gordon is a Jew, it does not matter to him. Akhmatova said that in her midst they did not know who a Jew was, it was not customary to ask about it. I suspect that the Jews in her midst knew perfectly well which of them were Jews.

Hypothetically, there are Jewish writers who write non-Jewish books, as well as vice versa. A novel by Eliza Orzeszko, a remarkable Polish writer, was published in the “Prose of Jewish Life” series. But the rules, not the exceptions, they are.

COMMENTS

Basic Techniques for Cropping a Photo in Photoshop How to Uncrop a Photo in Photoshop

Basic Techniques for Cropping a Photo in Photoshop How to Uncrop a Photo in Photoshop Which acrylic brushes are better to choose: little secrets of choosing the right one Using different piles

Which acrylic brushes are better to choose: little secrets of choosing the right one Using different piles What are the sizes of business cards?

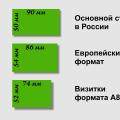

What are the sizes of business cards?