The evolution of the Russian hut. Four-wall, five-wall and six-wall. Traditional five-wall

In the morning the sun was shining, but only the sparrows screamed loudly - a sure sign of a blizzard. In the twilight, frequent snow fell, and when the wind picked up, it was so dusty that even an outstretched hand could not be seen. It raged all night, and the next day the storm did not lose strength. The hut was covered with snow to the top of the basement, on the street there are snowdrifts in human height - you can’t even go to the neighbors, and you can’t get out of the outskirts of the village at all, but you don’t really need to go anywhere, except perhaps for firewood in a woodshed. There will be enough supplies in the hut for the whole winter.

In the basement- barrels and tubs with pickles, cabbage, mushrooms and lingonberries, bags of flour, grain and bran for poultry and other livestock, bacon and sausages on hooks, dried fish; in the cellar potatoes and other vegetables are poured into piles. And there is order in the barnyard: two cows are chewing hay, with which the tier above them is littered to the roof, pigs are grunting behind a fence, a bird is dozing on a perch in a chicken coop fenced off in the corner. It's cool here, but there's no frost. Built of thick logs, carefully caulked walls do not let in drafts and keep the heat of animals, rotting manure and straw.

And in the hut itself, I don’t remember the frost at all - a hotly heated stove cools down for a long time. It’s just that the kids are bored: until the storm ends, you won’t get out of the house to play, to run. Babies are lying on the floor, listening to fairy tales that grandfather tells ...

The most ancient Russian huts - until the 13th century - were built without a foundation, almost a third buried in the ground - it was easier to save heat. They dug a hole in which they began to collect crowns of logs. Plank floors were still far away, and they were left earthen. On the hard-packed floor a hearth was laid out of stones. In such a semi-dugout, people spent winters together with domestic animals, which were kept closer to the entrance. Yes, and there were no doors, and a small inlet - just to squeeze through - was covered from the winds and cold weather with a shield of half-logs and a cloth canopy.

Centuries passed, and the Russian hut got out of the ground. Now it was placed on a stone foundation. And if on piles, then the corners rested on massive decks. Those who are richer they made roofs from tesa, the poorer peasants covered the huts with wood chips. And the doors appeared on forged hinges, and the windows were cut through, and the size of the peasant buildings increased markedly.

The traditional huts are best known to us, as they are preserved in the villages of Russia from the western to the eastern limits. This a five-wall hut, consisting of two rooms - a vestibule and a living room, or a six-wall when the actual living space is divided by another transverse wall into two. Such huts were erected in villages until very recently.

The peasant hut of the Russian North was built differently.

In fact, the northern hut is not just a house, but a module for the complete life support of the family of a few people during a long, harsh winter and a cold spring. A sort of spaceship on a joke, the ark, traveling not in space, but in time - from heat to heat, from harvest to harvest. Human habitation, premises for livestock and poultry, stores of supplies - everything is under one roof, everything is protected by powerful walls. Is that a woodshed and barn-hayloft separately. So they are right there, in the fence, it is not difficult to break a path to them in the snow.

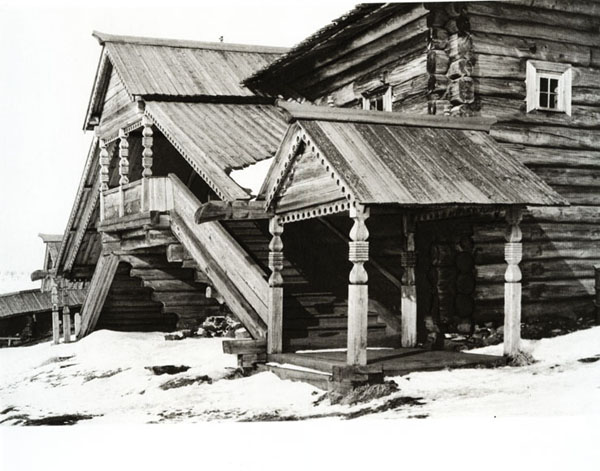

northern hut built in two tiers. Lower - economic, there is a barnyard and a storehouse of supplies - basement with a cellar. Upper - housing for people, upper room, from the word mountain, that is, high, because above. The warmth of the barnyard rises, people have known this since time immemorial. To get into the upper room from the street, the porch was made high. And, climbing it, I had to overcome a whole flight of stairs. But no matter how snowdrifts piled snowdrifts, they will not notice the entrance to the house.  From the porch, the door leads to the canopy - a spacious vestibule, it is also a transition to other rooms. Various peasant utensils are stored here, and in the summer, when it gets warm, they sleep in the hallway. Because it's cold. Through the canopy you can go down to the barnyard, from here - the door to the chamber. You just have to be careful when entering the chamber. To keep warm, the door was made low and the threshold high. Raise your legs higher and do not forget to bend down - an uneven hour will fill a bump on the lintel.

From the porch, the door leads to the canopy - a spacious vestibule, it is also a transition to other rooms. Various peasant utensils are stored here, and in the summer, when it gets warm, they sleep in the hallway. Because it's cold. Through the canopy you can go down to the barnyard, from here - the door to the chamber. You just have to be careful when entering the chamber. To keep warm, the door was made low and the threshold high. Raise your legs higher and do not forget to bend down - an uneven hour will fill a bump on the lintel.

A spacious basement is located under the upper room, the entrance to it is from the barnyard. They made basements with a height of six, eight, or even ten rows of logs - crowns. And having started to engage in trade, the owner turned the basement not only into storage, but also into a village trading shop - he cut through a window-counter for buyers to the street.

However, they were built differently. In the museum "Vitoslavlitsy" in Veliky Novgorod there is a hut inside, like an ocean ship: passages and transitions to different compartments begin behind the street door, and in order to get into the upper room, you need to climb up the ladder-ladder under the very roof.

You cannot build such a house alone, therefore in the northern rural communities a hut for the young - a new family - was set up the whole world. All the villagers built: they cut together and they carried timber, sawed huge logs, laid crown after crown under the roof, together they rejoiced at what had been built. Only when wandering artels of artisan carpenters appeared did they begin to hire them to build housing.

The northern hut from the outside seems huge, but there is only one dwelling in it - a room with an area of twenty meters, and even less. Everyone there lives together, old and young. There is a red corner in the hut, where icons and a lamp are hanging. The owner of the house sits here, guests of honor are also invited here.

The main place of the hostess is opposite the stove, called kut. And the narrow space behind the stove - closed. This is where the expression " huddle in a nook"- in a cramped corner or tiny room.

"It's light in my upper room..."- sung in a popular not so long ago song. Alas, this was not the case for a long time. For the sake of keeping warm, small windows in the upper room were cut down, they were covered with bull or fish bubbles or oiled canvas, which hardly let light through. Only in rich houses could one see mica windows. The plates of this layered mineral were fixed in curly bindings, which made the window look like a stained-glass window. By the way, there were even windows made of mica in the carriage of Peter I, which is kept in the collection of the Hermitage. In winter, plates of ice were inserted into the windows. They were carved on a frozen river or frozen in shape right in the yard. It came out brighter. True, it was often necessary to prepare new “ice glasses” instead of melting ones. Glass appeared in the Middle Ages, but as a building material the Russian village recognized it only in the 19th century.

Long time in the countryside, yes, and in the city stove huts were laid without pipes. Not because they didn’t know how or didn’t think of it, but all for the same reasons - as it were better to keep warm. No matter how you block the pipe with dampers, the frosty air still penetrates from the outside, chilling the hut, and the stove has to be heated much more often. The smoke from the stove got into the room and went out into the street only through small chimney windows under the very ceiling, which were opened for the duration of the firebox. Although the stove was heated with well-dried "smokeless" logs, there was enough smoke in the chamber. That is why the huts were called black or chicken.

Chimneys on the roofs of rural houses appeared only in the XV-XVI centuries, yes, and then where the winters were not too severe. Huts with a pipe were called white. But at first they did not make pipes of stone, but knocked down from wood, which often caused a fire. Only at the beginning XVIII century Peter I by special decree ordered in the city houses of the new capital - St. Petersburg, stone or wooden, to put stoves with stone chimneys.

Later, in the huts of wealthy peasants, in addition to Russian ovens, in which food was prepared, began to appear brought to Russia by Peter I dutch ovens, convenient for their small size and very high heat dissipation. Nevertheless, stoves without chimneys continued to be laid in the northern villages until the end of the 19th century.

The stove is the warmest sleeping place - a stove bench, which traditionally belongs to the oldest and youngest in the family. A wide shelf stretches between the wall and the stove - a shelf. It is also warm there, so they put it on the floor sleep children. Parents were located on the benches, and even on the floor; the bed time has not yet come.

Why were children in Russia punished, put in a corner?

What did the corner itself mean in Russia? Each house in the old days was a small church, which had its own Red Corner (Front Corner, Holy Corner, Goddess), with icons.

It is in this Red Corner parents set their children to pray to God for their misdeeds and in the hope that the Lord would be able to reason with a naughty child.

Russian hut architecture gradually changed and became more complex. There were more living quarters. In addition to the vestibule and the upper room appeared in the house room - a really bright room with two or three large windows already with real glasses. Now most of the family's life took place in the room, and the upper room served as a kitchen. The room was heated from the rear wall of the furnace.

And wealthy peasants shared a vast a residential log cabin with two walls crosswise, thus blocking four rooms. Even a large Russian stove could not heat the entire room, and here it was necessary to put an additional one in the room farthest from it dutch oven.

Bad weather rages for a week, and under the roof of the hut it is almost inaudible. Everything goes on as usual. The hostess has the most trouble: in the early morning to milk the cows and pour grain for the birds. Then steam the bran for the pigs. Bring water from a village well - two buckets on a yoke, one and a half pounds with a total weight, yes, and you have to cook food, feed your family! The kids, of course, help in any way they can, as it has always been customary.

Men have fewer worries in winter than in spring, summer and autumn. The owner of the house is the breadwinner- Works tirelessly all summer from dawn to dusk. He plows, mows, reaps, threshes in the field, cuts, saws in the forest, builds houses, gets fish and forest animals. As the owner of the house earns, so his family will live all winter until the next warm season, because winter for men is a time of rest. Of course, one cannot do without male hands in a rural house: fix what needs to be repaired, chop and bring firewood into the house, clean the barn, make a sleigh, and arrange dressage for horses, take the family to the fair. Yes, in a village hut there are many things that require strong male hands and ingenuity, which neither a woman nor children can do.

The northern huts, cut down by skillful hands, stood for centuries. Generations changed, and the ark houses still remained a reliable refuge in harsh natural conditions. Only the mighty logs darkened with time.

Museums of wooden architecture Vitoslavlitsy" in Veliky Novgorod and Small Korely» near Arkhangelsk there are huts whose age has exceeded one and a half centuries. Ethnographers searched for them in abandoned villages and ransomed them from the owners who moved to the cities.

Then carefully dismantled transported to the museum territory and restored in its original form. This is how they appear before numerous sightseers who come to Veliky Novgorod and Arkhangelsk.

***

crate- a rectangular one-room log house without outbuildings, most often 2 × 3 m in size.

Cage with oven- hut.

Podklet (podklet, podzbitsa) - the lower floor of the building, located under the cage and used for economic purposes.

The tradition of decorating houses with carved wooden architraves and other decorative elements did not originate in Russia from scratch. Initially, wooden carving, like ancient Russian embroidery, had a cult character. The ancient Slavs applied to their homes pagan signs designed to protect dwelling, provide fertility and protection from enemies and natural elements. No wonder in stylized ornaments you can still guess signs denoting sun, rain, women raising their hands to the sky, sea waves, depicted animals - horses, swans, ducks or a bizarre interweaving of plants and outlandish paradise flowers. Further, the religious meaning of the wooden carving was lost, but the tradition of giving an artistic look to various functional elements of the facade of the house has remained to this day.

In almost every village, village or city, you can find amazing examples of wooden lace decorating the house. Moreover, in different areas there were completely different styles of wooden carving for decorating houses. In some areas, predominantly blind carving is used, in others sculptural, but mostly houses are decorated with carved carvings, as well as its variety - carved decorative wooden invoice.

In the old days, in various regions of Russia, and even in different villages, carvers used certain types of carving and ornamental elements. This is clearly visible if we look at photographs of carved architraves made in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In one village, certain elements of carving were traditionally used on all houses, in another village, the motifs of carved platbands could be completely different. The farther these settlements were from each other, the more the carved platbands on the windows differed in appearance. The study of old house carvings and architraves in particular gives ethnographers a lot of material to study.

In the second half of the 20th century, with the development of transport, printing, television and other means of communication, ornaments and carvings that were previously inherent in one particular region began to be used in neighboring villages. A widespread mixing of wood carving styles began. Looking at photographs of modern carved architraves located in one settlement, one can be surprised at their diversity. Maybe it's not so bad? Modern cities and towns are becoming more vibrant and unique. Carved architraves on the windows of modern cottages often incorporate elements of the best examples of wooden decor.

Boris Rudenko. For more details, see: http://www.nkj.ru/archive/articles/21349/ (Science and Life, Russian hut: an ark among the forests)

Russian house of five-walls in central Russia. A typical three-slope roof with a light. Five-wall with a cut along the house

These examples, I think, are quite enough to prove that this type of houses really exists and that it is widespread in the traditionally Russian regions. It was somewhat unexpected for me that this type of house prevailed until recently on the coast of the White Sea. Even if we admit that I am wrong, and this style of houses came to the north from the central regions of Russia, and not vice versa, it turns out that the Slovenes from Lake Ilmen have nothing to do with the colonization of the White Sea coast. There are no houses of this type in the Novgorod region and along the Volkhov River. Strange, isn't it? And what kind of houses did Novgorod Slovenes build from time immemorial? Below I give examples of such houses.

Slovenian type of houses

|

|

In this photo we see a gable roof, which allows us to attribute this house to the Slovenian type. A house with a high basement, decorated with carvings typical of Russian houses. But the rafters lie on the side walls, like a barn. This house was built in Germany at the beginning of the 19th century for Russian soldiers sent by the Russian tsar to help Germany. Some of them stayed in Germany for good, the German government, as a token of gratitude for their service, built such houses for them. I think that the houses were built according to the sketches of these soldiers in the Slovenian style |

This is also a house from the German soldier series. Today in Germany, these houses are part of the open-air museum of Russian wooden architecture. The Germans earn money from our traditional applied arts. In what perfect condition do they keep these houses! And we? We don't appreciate what we have. We turn our noses up, we look at everything overseas, we do European-quality repairs. When will we start repairing the Rus and repair our Russia? |

In my opinion, these examples of houses of the Slovenian type are enough. Those interested in this issue can find a lot of evidence for this hypothesis. The essence of the hypothesis is that real Slovenian houses (huts) differed from Russian huts in a number of ways. It is probably stupid to talk about which type is better, which is worse. The main thing is that they are different from each other. The rafters are set differently, there is no cut along the house at the five-walls, the houses, as a rule, are narrower - 3 or 4 windows along the front, the platbands and lining of the houses of the Slovenian type, as a rule, are not sawn (not openwork) and therefore do not look like lace . Of course, there are houses of a mixed type of construction, somewhat similar to Russian-type houses in the setting of rafters and the presence of cornices. The most important thing is that both Russian and Slovenian types of houses have their own areas. Houses of the Russian type in the territory of the Novgorod region and the west of the Tver region are not found or are practically not found. I didn't find them there.

Finno-Ugric type of houses

The Finno-Ugric type of houses is, as a rule, five-walled with a longitudinal cut and a significantly larger number of windows than houses of the Slovenian type. It has a log pediment, in the attic there is a room with log walls and a large window, which makes the house seem to be two-story. The rafters are attached directly to the wall, and the roof hangs over the walls, so this type of house does not have a cornice. Often houses of this type consist of two joined log cabins under one roof. |

The middle course of the Northern Dvina is above the mouth of the Vaga. This is how a typical house of the Finno-Ugric type looks like, which for some reason ethnographers stubbornly call northern Russian. But it is more widely distributed in the Komi Republic than in Russian villages. This house in the attic has a full-fledged warm room with log walls and two windows. |

And this house is located in the Komi Republic in the Vychegda River basin. It has 7 windows on the facade. The house is made of two four-wall log cabins connected to each other by a log capital insert. The pediment is timbered, which makes the attic of the house warm. There is an attic room, but it has no window. The rafters are laid on the side walls and hang over them. |

The village of Kyrkanda in the southeast of the Arkhangelsk region. Please note that the house consists of two log cabins placed close to each other. The pediment is log, in the attic there is an attic room. The house is wide, so the roof is quite flattened (not steep). There are no carved platbands. The rafters are installed on the side walls. There was also a house consisting of two log cabins in our village of Vsekhsvyatskoye, only it was of the Russian type. As children, playing hide-and-seek, I once climbed out of the attic into the gap between the log cabins and barely crawled back out. It was very scary... |

House of the Finno-Ugric type in the east of the Vologda region. From the attic room in this house you can go to the balcony. The front roof overlap is such that you can stay on the balcony even in the rain. The house is tall, almost three-story. And in the back of the house there are still the same three huts, and between them there is a huge story. And it all belonged to the same family. Perhaps that is why there were many children in the families. The Finno-Ugric peoples lived splendidly in the past. Today, not every new Russian has such a large cottage |

Kinerma village in Karelia. The house is smaller than the houses in the Komi Republic, but the Finno-Ugric style is still discernible. There are no carved platbands, so the face of the house is more severe than that of Russian-type houses |

Komi Republic. Everything suggests that we have a house built in the Finno-Ugric style. The house is huge, it accommodates all utility rooms: two winter residential huts, two summer huts - upper rooms, pantries, a workshop, a canopy, a barn, etc. You don't even have to go outside in the morning to feed the cattle and poultry. During the long cold winter this was very important. |

Republic of Karelia. I want to draw attention to the fact that the type of houses in Komi and Karelia is very similar. But these are two different ethnic groups. And between them we see houses of a completely different type - Russian. I note that Slovenian houses are more like Finno-Ugric than Russian. Strange, isn't it? |

Houses of the Finno-Ugric type are also found in the northeast of the Kostroma region. This style has probably been preserved here since the time when the Finno-Finnish tribe of Kostroma had not yet become Russified. The windows of this house are on the other side, and we see the back and side walls. According to the flooring, one could drive into the house on a horse and cart. Convenient, isn't it? |

On the Pinega River (the right tributary of the Northern Dvina), along with houses of the Russian type, there are also houses of the Finno-Ugric type. The two ethnic groups have been coexisting here for a long time, but still retain their traditions in the construction of houses. I draw your attention to the absence of carved platbands. There is a beautiful balcony, a room - a light room in the attic. Unfortunately, such a good house was abandoned by the owners, who were drawn to the city couch potato life. |

Probably enough examples of houses of the Finno-Ugric type. Of course, at present, the traditions of building houses are largely lost, and in modern villages and towns they build houses that differ from the ancient traditional types. Everywhere in the vicinity of our cities today we see ridiculous cottage development, testifying to the complete loss of our national and ethnic traditions. As can be understood from these photographs, borrowed by me from many dozens of sites, our ancestors did not live cramped, in environmentally friendly spacious, beautiful and comfortable houses. They worked happily, with songs and jokes, they were friendly and not greedy, there are no blank fences near houses anywhere in the Russian North. If someone's house burned down in the village, then the whole world built a new house for him. I note once again that there were no Russian and Finno-Ugric houses near and today there are no deaf high fences, and this says a lot.

Polovtsian (Kypchak) type of houses

I hope that these examples of houses built in the Polovtsian (Kypchak) style are enough to prove that such a style really exists and has a certain distribution area, including not only the south of Russia, but also a significant part of Ukraine. I think that each type of house is adapted to certain climatic conditions. There are many forests in the north, it is cold there, so the inhabitants build huge houses in the Russian or Finno-Ugric style, in which people live, livestock, and belongings are stored. There is enough forest for both walls and firewood. There is no forest in the steppe, there is little of it in the forest-steppe, so the inhabitants have to make adobe, small houses. A big house is not needed here. Livestock can be kept in a paddock in summer and winter, inventory can also be stored outdoors under a canopy. A person in the steppe zone spends more time outdoors than in a hut. That's how it is, but in the floodplain of the Don, and especially the Khopra, there is a forest from which it would be possible to build a hut and stronger and bigger, and make a roof for a horse, and arrange a light room in the attic. But no, the roof is made in the traditional style - four-pitched, so the eye is more familiar. Why? And such a roof is more resistant to winds, and winds in the steppe are much stronger. The roof will be easily blown away by a horse during the next snowstorm. In addition, it is more convenient to cover a hipped roof with straw, and straw in the south of Russia and Ukraine is a traditional and inexpensive roofing material. True, the poor also covered their houses with straw in central Russia, even in the north of the Yaroslavl region in my homeland. As a child, I still saw old thatched houses in All Saints. But those who were richer covered their houses with shingles or boards, and the richest - with roofing iron. I myself had a chance, under the guidance of my father, to cover our new house and the house of an old neighbor with shingles. Today, this technology is no longer used in the villages, everyone has switched to slate, ondulin, metal tiles and other new technologies.

By analyzing the traditional types of houses that were common in Russia quite recently, I was able to identify four main ethno-cultural roots from which the Great Russian ethnos grew. There were probably more daughter ethnic groups that merged into the ethnic group of Great Russians, since we see that the same type of houses was characteristic of two, and sometimes even three related ethnic groups living in similar natural conditions. Surely, in each type of traditional houses, subtypes can be distinguished and associated with specific ethnic groups. Houses in Karelia, for example, are somewhat different from houses in Komi. And the houses of the Russian type in the Yaroslavl region were built a little differently than the houses of the same type on the Northern Dvina. People have always strived to express their individuality, including in the arrangement and decoration of their homes. At all times there were those who tried to change or denigrate traditions. But exceptions only underline the rules - everyone knows this well.

I will consider that I wrote this article not in vain if in Russia they build fewer ridiculous cottages in any style, if someone wants to build their new house in one of the traditional styles: Russian, Slovenian, Finno-Ugric or Polovtsian. All of them have now become all-Russian, and we are obliged to preserve them. An ethno-cultural invariant is the basis of any ethnic group, perhaps more important than a language. If we destroy it, our ethnic group will degrade and disappear. I saw how our compatriots who emigrated to the USA cling to ethno-cultural traditions. For them, even the production of cutlets turns into a kind of ritual that helps them feel that they are Russians. Patriots are not only those who lie down under the tanks with bundles of grenades, but also those who prefer the Russian style of houses, Russian felt boots, cabbage soup and borscht, kvass, etc.

In the book of a team of authors edited by I.V. Vlasov and V.A. Tishkov "Russians: history and ethnography", published in 1997 by the publishing house "Nauka", there is a very interesting chapter on rural residential and economic development in Russia in the 12th - 17th centuries. But the authors of the chapter L.N. Chizhikov and O.R. Rudin, for some reason, paid very little attention to Russian-type houses with a gable roof and a light room in the attic. They consider them in the same group as Slovenian-type houses with a gable roof hanging over the side walls.

However, it is impossible to explain how the houses of the Russian type appeared on the shores of the White Sea and why they are not in the vicinity of Novgorod on Ilmen, based on the traditional concept (stating that the White Sea was controlled by Novgorodians from Ilmen). This is probably why historians and ethnographers do not pay attention to Russian-type houses - there are none in Novgorod. The book by M. Semenova "We are Slavs!", published in 2008 in St. Petersburg by the Azbuka-classika publishing house, contains good material on the evolution of the Slovenian-type house.

|

According to the concept of M. Semenova, the original dwelling of the Ilmen Slovenes was a semi-dugout, almost completely buried in the ground. Only a slightly gable roof rose above the surface, covered with poles, on which a thick layer of turf was laid. The walls of such a dugout were log. Inside there were benches, a table, a lounger for sleeping. Later, an adobe stove appeared in the semi-dugout, which was heated in a black way - the smoke went into the dugout and went out through the door. After the invention of the stove, it became warm in the dwelling even in winter, it was possible not to dig into the ground. The Slovenian house "began to crawl out" from the ground to the surface. A floor appeared from hewn logs or from blocks. In such a house it became cleaner and brighter. Earth did not fall from the walls and from the ceiling, it was not necessary to bend into three deaths, it was possible to make a higher door.

I think that the process of turning a semi-dugout into a house with a gable roof took many centuries. But even today, the Slovenian hut bears some features of the ancient semi-dugout, at least the shape of the roof has remained gable. |

Medieval house of the Slovenian type on a residential basement (essentially two-story). Often on the ground floor there was a barn - a room for livestock) |

I suppose that the most ancient type of house, undoubtedly developed in the north, was the Russian type. Houses of this type are more complex in terms of roof structure: it is three-sloped, with a cornice, with a very stable position of the rafters, with a chimney-heated room. In such houses, the chimney in the attic made a bend about two meters long. This bend of the pipe is figuratively and accurately called "boar", on such a hog in our house in Vsekhsvyatsky, for example, cats warmed themselves in winter, and it was warm in the attic from it. In a Russian-type house, there is no connection with a semi-dugout. Most likely, such houses were invented by the Celts, who penetrated the White Sea at least 2 thousand years ago. It is possible that on the White Sea and in the basin of the Northern Dvina, Sukhona, Vaga, Onega and the upper Volga lived the descendants of those Aryans, some of whom went to India, Iran and Tibet. This question remains open, and this question is about who we Russians are - newcomers or real natives? When a connoisseur of the ancient language of India, Sanskrit, got into a Vologda hotel and listened to the dialect of women, he was very surprised that the Vologda women spoke some kind of corrupted Sanskrit - the Russian language turned out to be so similar to Sanskrit. Houses of the Slovene type arose as a result of the transformation of the semi-dugout as the Ilmen Slovenes moved north. At the same time, the Slovenes adopted a lot (including some methods of building houses) from the Karelians and Vepsians, with whom they inevitably came into contact. But the Varangians Rus came from the north, pushed apart the Finno-Ugric tribes and created their own state: first North-Eastern Russia, and then Kievan Rus, moving the capital to warmer climes, while pushing the Khazars. But those ancient states in the 8th - 13th centuries had no clear boundaries: those who paid tribute to the prince were considered to belong to this state. The princes and their squads fed by robbing the population. By our standards, they were ordinary racketeers. I think that the population often passed from one such racketeer-sovereign to another, and in some cases the population "fed" several such "sovereigns" at once. Constant skirmishes between princes and chieftains, constant robbery of the population in those days were the most common thing. The most progressive phenomenon in that era was the subjugation of all the petty princes and chieftains by one sovereign, the suppression of their freedom and the imposition of a hard tax on the population. Such a salvation for the Russians, Finno-Ugric peoples, Krivichi and Slovenes was their inclusion in the Golden Horde. Unfortunately, our official history is based on chronicles and written documents compiled by the princes or under their direct supervision. And for them - the princes - to obey the supreme authority of the Golden Horde king was "worse than a bitter radish." So they called this time a yoke. |

A peasant hut made of logs has been considered a symbol of Russia from time immemorial. According to archaeologists, the first huts appeared in Russia 2 thousand years ago BC. For many centuries, the architecture of wooden peasant houses remained practically unchanged, combining everything that every family needed: a roof over their heads and a place where you can relax after a hard day's work.

In the 19th century, the most common plan of a Russian hut included a dwelling (hut), a canopy and a crate. The main room was a hut - a heated living space of a square or rectangular shape. A crate was used as a storage room, which was connected to the hut at the expense of a canopy. In turn, the canopy was a utility room. They were never heated, so they could only be used as living quarters in the summer. Among the poor strata of the population, a two-chamber layout of the hut, consisting of a hut and a vestibule, was common.

The ceilings in wooden houses were flat, they were often hemmed with painted hemp. The floors were made of oak bricks. The decoration of the walls was carried out with the help of red board, while in rich houses the decoration was supplemented with red leather (less wealthy people usually used matting). In the 17th century, ceilings, vaults and walls began to be decorated with paintings. Benches were placed around the walls under each window, which were securely fastened directly to the structure of the house itself. Approximately at the level of human height above the benches along the walls, long shelves made of wood, which were called crows, were equipped. On the shelves located along the room, they kept kitchen utensils, and on others - tools for men's work.

Initially, the windows in Russian huts were portage, that is, viewing windows that were cut in adjacent logs half a log up and down. They looked like a small horizontal slot and were sometimes decorated with carvings. They closed the opening (“clouded”) with the help of boards or fish bubbles, leaving a small hole (“peeper”) in the center of the valve.

After some time, the so-called red windows, with a frame, framed by jambs, became popular. They had a more complex design than portage ones, and were always decorated. The height of the red windows was at least three diameters of a log in a log house.

In poor houses, the windows were so small that when they were closed, the room became very dark. In rich houses, windows were closed from the outside with iron shutters, often using pieces of mica instead of glass. From these pieces it was possible to create various ornaments, painting them with images of grass, birds, flowers, etc. with the help of paints.

When teachers told us that primitive people lived in caves, I was very surprised: after all, in the village, my grandparents have no caves at all, no mountains - how can they? where did they live? or we did not have primitive people? As for the completely primitive ones, I don’t know, but nevertheless, the sites of ancient tribes were dug up a few tens of kilometers away. It's simple: they lived in huts (in summer) and in dugouts (in winter), inside the dwelling there was a hearth that was "kept by a woman" while a man ran after a mammoth. But then iron appeared - a man made an ax, began to cut down trees and build a wooden dwelling - a quadrangular structure made of logs, the heart of which becomes a stove: at first it was completely antediluvian, which then turned into a real, Russian one. And this house was named hut (from the verb "drown", the old Russian "truth").

Early 1960s.

In our forest-rich country, the hut was destined to exist to this day.

"The white hut mainly consists of a four-walled log house of 7-10 arshins, with three windows to the street, covered more often with straw, less often with shingles or iron, and with one door in the back wall."

By the way, in the upper photo on the left you can see that part of the roof has not yet been covered with slate, and there it is - split wooden planks, in fact, "wooden tiles". In the photo below you can see how the same shingle (as in the top photo) looks from the attic today.

If someone is confused by the phrase "white hut", then I will explain that there were also "black huts" (chicken huts) - without a chimney and they were heated "in black" when the smoke covered the room and the door opened wide. By the way, in 1922, local historians say that in our area several black huts still existed - of course, not quite the same as in the picture))

I didn't understand the expression before. "hut-five-wall" . What it is? There were almost no five-walls in our village. It turned out that these are actually two huts under one roof, connected by one common wall - as in the bottom photo. In a five-wall oven, the stove is placed so that it heats both halves - near the main adjacent wall.

In this case - one half serves as a kitchen and dining room, and the other - a clean half - a living room and bedroom for privileged family members. Such five-walls could be built in width (photo above) or in length (photo below - there, it seems, even some kind of "seven-wall" - 3 internal walls).

Actually, the huts themselves, in principle, are all of the same type - a "four-cornered cage", but the owners wanted to make their house special, so they tried to decorate the hut from the outside with carvings of platbands on the windows. Here, everyone tried their best.

photo: http://mama.tomsk.ru/forums/viewtopic.php?f=48&t=178067&view=print

In addition to the gable roof, they also made a three-slope one with a structure "in the form of a carved booth with a dormer window inserted into it."

Almost a quarter of the hut is occupied by a stove and structures around it - floors, ladders, steps, pantries - "near it is a wooden golbets, from the stove shoulder to the front wall there is a plank partition dividing the log house at the bottom of unequal halves."(From a local history essay, 1922)

golbets-

this is the construction at the stove and for climbing the stove, designed differently for everyone: in the form of a fence or a closet with doors, a manhole and steps. For example, as shown below.

Inside the hut, a light partition is made of boards, which often does not reach the ceiling - so that warm air circulates along the top. Everything next to the stove is a kitchen, utility and dining area, behind the partition - "in front" - everything is in one: they sleep there, receive guests, relax, etc. Inviting guests to pass, we said: "Come to the front."

http://www.yaroslavskiy-kray.com/531/508-krestyanskaya-semya-za-obedom.jpg.html

"In the front corner there is a goddess with icons and a lamp, a table, along the walls of the shop, above them shelves (half-tops), to the back wall on a beam of bed, at the bottom there is a conic or a bed." (From a local history essay, 1922)

The corner where the icons stood was called red. The first thing for those who entered the hut is to cross themselves on the icons, and then to say hello to the owners. On church holidays, a lampada is lit in front of the icons - an oil lamp with a wick.

Since the main wealth of a peasant family is children, there was always a strong hook for pitching (cradles) on the ceiling. According to the stories of the aunt, they had a wicker cradle in their family - perhaps, such as in the photo.

photo http://forum.globus.tut.by/viewtopic.php?p=9397&sid=

What else was in the peasant's hut? A cupboard with dishes, a chest could stand, "patrets" hung in frames, pictures on the wall, a light bulb (formerly a hanging kerosene lamp) above the table, a mirror in the wall between the windows. In the photo below - we had a mirror in such a frame - I remember it from early childhood. And it was found last year - I saved it, one can say: in the village they don't stand on ceremony with "junk" - they burn everything. I'll try to fix it this summer. It’s a pity there is no mirror itself - it was an old, old, distorting reflection, with stunning divorces and cracks, with iridescent drawings on ancient amalgam. It could be considered as a work of art ...

I have long wanted to photograph some of the remaining rare home-made furniture, miraculously survived to this day. As soon as I manage to do this, I will definitely show and tell.

In addition to the Russian stove, to maintain heat in the house for the winter, an iron stove was installed with iron pipes leading to the chimney of the Russian stove.

She was stoked almost all day long. Village children loved to bake potatoes on it - they glued cut potatoes to a metal surface - and waited. This was the grill...

Behind every peasant house - yard

(for livestock), which is a large barn with a two or three-pitched roof. The yard is connected to the house by an unheated structure, which is called the entrance hall (and in our case - bridge

). There is fenced off lumber room

(fenced off utility room), there may be pantries, etc.

The cattle yard was dark before the advent of electricity, and cold in winter. It was divided into barns for cattle: in our yard, a cow was allocated a personal capital (made of logs) "room" with a door. The sheepshed was simpler - it was fenced off with boards: they are in the "flock", they have wool - they are warm ...

If the owners of the house, where the "yard" of the 60-70s is preserved, will allow me to take photographs, then I will definitely post them.

Until the 70s of the 19th century, the lighting in the villages was torch. Tallow candles were used as an aid (for going out into the yard to cattle and other things). In each hut there was svetets ”, which consisted of a stand with iron horns and a trough. Of course, I didn’t find Svetets)) Because since 1876 in our region they switched to kerosene lamps.

photo http://reviewdetector.ru/lofiversion/index.php?t175877.html

At first, lamps without "smoker" glasses were used, then real lamps with glasses appeared. About the "archer and oil lamps" they remembered in the revolution - for some reason there was no kerosene. And from the 1920s, "electrification" slowly began - as a bonus to Soviet power (remember: "Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country"?)

I didn’t even find a kerosene lamp, however, I didn’t wait for communism either))

But I found an artifact.

Those who made the transition from kerosene to electricity told how miraculous the electric light seemed after the kerosene lamp. And here is a snapshot of the 50s - this is what a peasant hut looked like in Soviet times. In the red corner, instead of icons, some had portraits of leaders. Then the walls will begin to paint, upholstered with planks and even wallpaper.

photo by D. Baltermants

In our family, portraits of leaders have not replaced icons. But everything else is similar - curtains, a clock in the same place, and a receiver under a lace napkin.

During these years, the famous Soviet radio receiver appeared. Star" , the design of which was "torn off" from the French " Excelsior-52" issue of 1952. What is called: feel the difference - in the photo above is our "Star", and below - French Excelsior ".

Photo: http://rw6ase.narod.ru

It was him that my grandparents bought in the 50s, it was for him that I listened to “Baby Monitor”, “Theater at the Microphone” all my childhood, it was his gurgling, hissing and whistling that I took for alien space signals. Yes, I was still that dreamer)) They never got a TV - they simply didn’t need it.

"Villages" in their layout, they are very similar to each other and consist for the most part of two orders of wooden huts, built one against the other. There are some exceptions to this, where the buildings are placed in the form of a quadrangle or in several streets and alleys. Behind the yards are outbuildings: cellars, barns, sheds, behind a vegetable garden or a garden, barns, threshers. There are no baths anywhere. The street is mostly free from outbuildings, with the exception of chapels, schools, a fire station in the village and a church in the village. "(From a local history essay, 1922)

But two-story wooden, as well as stone peasant houses - in our district were a rare exception. We didn't have any in the village. This was explained by the fact that stone buildings were much damper and colder than wooden ones. In addition - there was a lot of wood - it was easier to harvest wood than to mold and burn bricks. But the disadvantage of wooden huts is their high fire hazard. Burned. And they are burning - this winter in our village one house burned down.

And I don’t know anything about “wintering” to be honest. But local historians write:

"Often, behind the front house under the courtyard roof there is a traditional winter hut, where the family goes with the first frosts for the winter and leaves it for Easter with the transition to the summer hut. Wintering is usually a small hut, thatched with straw, which is also done, without exception, near all houses where they hibernate. From this, in winter, there is even less light in the house than it should be." (From a local history essay, 1922)

How many walls does a Russian hut have? Four? Five? Six? Eight? All answers are correct because the question is a trick. The fact is that in Russia different huts were built, differing from each other in purpose, prosperity of the owners, region and even the number of walls! So, for example, the hut that everyone saw in childhood in illustrated books with folk tales (the same one on chicken legs) is called a four-wall. Of course, a real four-walled house does not have chicken legs, but otherwise it looks exactly like this: a log house with four walls with pretty windows and a large roof.

But if with four walls everything is obvious and understandable, what does a five-walled hut look like? Where is this mysterious fifth wall located? Surprisingly, even after examining the famous Russian five-wall from all sides and having been inside, far from everyone succeeds in showing the fifth wall in the hut correctly. The options are called different. Sometimes they even say that the fifth wall is the roof. But it turns out that in Russia the fifth wall is called the one that is located inside the hut and divides the huge house into two living quarters. The same wall that separates the non-residential vestibule from the living quarters is not considered either the fifth or the sixth wall. Legitimate question: why?

As you know, the huts were built according to the "crowns": they laid in turn all the logs of one horizontal row, which means that all the walls in the house - four external and one internal - were erected simultaneously. But the canopy has already been completed separately. The interior of the hut was divided into two parts: the upper room and the living room, in which they put the stove and cooked food. The upper room was not specially heated, but was considered a front room in which it was possible to receive guests or gather with the whole family on the occasion of the holiday.

In many regions, even when peasant children grew up and started their own families, they continued to live with their parents, and then the five-wall building became a two-family house. An additional entrance was cut into the house, a second stove was installed, and a second vestibule was completed. In the five-wall ETHNOMIR you will see a special, modified Russian stove with two fireboxes, which heats both rooms, and an unusual double porch.

The five-wall is considered a large, rich hut. Only an artisan owner who knows how and loves to work could build something like this, so we set up a craft workshop in the five-wall ETNOMIR and conduct master classes dedicated to the traditional Slavic doll.

It may seem incredible, but historians and ethnographers have more than 2.5 thousand dolls of Russia: play, ritual, amulets. In our five-wall you will see over a hundred different dolls made from shreds, bast, straw, ash and other improvised, everyday materials of peasant life. And each doll has its own story, its own interesting story and its own purpose. Which one will touch your soul? A girl-woman, a pity, a column, a twist, a herbalist, a comforter, or maybe lovebirds? Order a master class "Home and family amulet dolls"! You will hear the stories of some dolls, marvel at the wisdom of the ancestors and their skill, make your own memorable souvenir: a patchwork angel for happiness, a homemade carnival, a small grain for prosperity in the house - or a patty for peace and harmony in your family. And the guardian of culture will tell you why it is more correct to make many dolls without scissors, why they do not have a face, and how exactly the good thoughts and faith with which our foremothers made dolls helped them in life.

Basic Techniques for Cropping a Photo in Photoshop How to Uncrop a Photo in Photoshop

Basic Techniques for Cropping a Photo in Photoshop How to Uncrop a Photo in Photoshop Which acrylic brushes are better to choose: little secrets of choosing the right one Using different piles

Which acrylic brushes are better to choose: little secrets of choosing the right one Using different piles What are the sizes of business cards?

What are the sizes of business cards?